Giving voice to the children adopted out of S Korea

SEOUL - Sent to the Netherlands for adoption when she was just three years old, Ms Simone Huits, now 32, grew up in a loving Dutch family and was starting her own wine-import business.

But she left it all behind for a South Korean man - her biological brother.

In 2011, she flew thousands of kilometres to Seoul to live with her older sibling, with whom she had reunited seven years earlier when she first visited her birth country as an adult, to join an adoptee programme to learn about the Korean language and culture.

"He asked me to come to Korea and live with him. We got along very well," she said, adding that this was despite the fact that her brother speaks broken English and she does not understand Korean well.

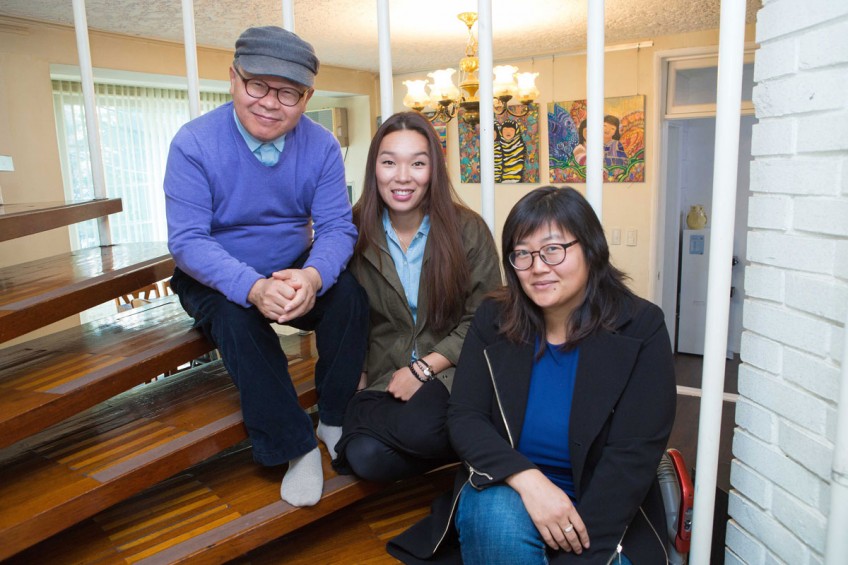

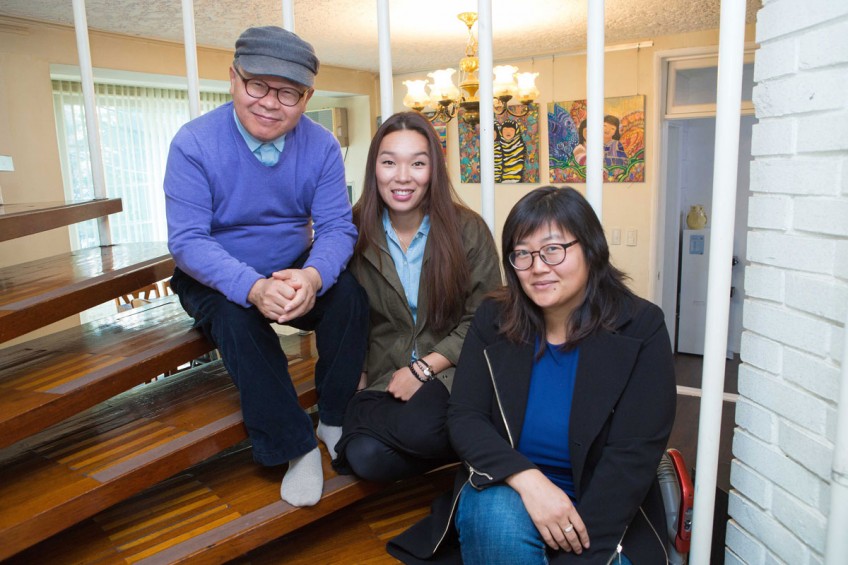

Four years on, Ms Huits is still living in Seoul, teaching English part-time at a private school and working for KoRoot, a non-governmental organisation (NGO) that promotes the rights of adoptees.

Born Eun Mi, she is among a growing group of international adoptees who have returned to South Korea in search of their roots and, in the process, are giving voice to the overlooked party in the adoption process.

You can take a child out of Korea, but you cannot take Korea out of a child - this old adage rings true even for adoptees who may have little memory of their birth countries.

Korea Adoption Services (KAS), which was started by the government in 2012 to help adoptees find their birth families, has seen a spike in requests for birth records, from 258 in 2012 to more than 1,600 in the first eight months of this year.

But the reality can be disheartening - only 14.7 per cent of birth-search requests made to the KAS in the past three years have yielded positive results.

About 200,000 Korean children have been given up for adoption and sent overseas - mainly to the United States and Europe - in the past six decades, beginning with war orphans and bi-racial babies in the poverty-stricken days after the Korean War of 1950-1953.

As the country grew strong economically and the government started tightening laws on adoption, figures for international adoption have fallen in recent years, from 2,101 children in 2005 to 535 last year, according to Health Ministry data.

About 90 per cent of the children are born to unwed mothers, a stigmatised group who tend to draw harsh criticism and social scrutiny, as pre-marriage pregnancy is considered immoral behaviour by conservative South Koreans. Abortion is illegal in South Korea, so giving up a child for adoption is deemed a better option than raising the child single-handedly.

While overseas adoption used to make up 70 per cent of all adoption in South Korea, government efforts to promote domestic adoption have closed the gap. Last year, local adoptions numbered 637, higher than the overseas figure.

FEELING OF ALIENATION

But international adoption is not always the better option for babies of unwanted pregnancies or orphans.

While some adoptees, like Ms Huits, grow up in a loving environment and get ample opportunities to excel, others end up in abusive families and lead a life full of struggles. What they may find in common is a feeling of alienation growing up, that they do not belong because of their looks.

Ms Annika Rump, 31, was adopted by a German couple after she was found in front of a police station in Seoul when she was five or six months old. Growing up in a small German village, she was acutely aware of how different she was from her three blonde-haired, blue-eyed older siblings.

"I've always had to explain myself, why I have a German name but don't look German, why I can speak German so well. You get fed up after a while," she said.

Ms Huits, who grew up in a small Dutch town, recalled: "All the children wanted to touch me because I looked different. It was scary and overwhelming."

Although adoption has been widely promoted as a "good thing" that gives an unwanted child a home, studies have shown that adoptees, who have to cope with identity issues and racism, are more likely to develop psychological problems and face a higher risk of suicide, compared with non-adoptees.

Reverend Kim Do Hyun was doing pastoral work at a church in Switzerland in 1993 when he attended the funeral of a 24-year-old Korean adoptee who left behind a note that read: "I'm looking for my birth mother." He became more involved with Korean adoptees there and wrote a thesis on adoption.

In 2004, he returned to Seoul to help run KoRoot, which he said is focused on challenging the government to change the child-raising system.

"International adoption is a failure of the South Korean government and society to raise a child. It is forced separation that can cause trauma to the mum and child," he said, adding that the country should keep all its babies since its birth rate is low.

Located in central Jongno district, in a two-storey house donated by its chairman Kim Gil Ja, KoRoot also operates a small guesthouse for returning adoptees. Up to 300 adoptees stay at KoRoot - which means Korean Root - every year. Some of them leave after a short stay, while others have stayed on in South Korea to learn their mother tongue, find work, or resettle.

If guests want to find their birth parents, KoRoot will refer them to KAS or NGOs such as Global Overseas Adoptees' Link as well as Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea, which were founded by adoptees to help fellow adoptees.

Ms Rump, who was staying at KoRoot when this reporter visited, said she felt a strong urge to take a four-month sabbatical from her human resource job in Cologne to come to Seoul in mid-September on a "personal discovery trip".

While she has been travelling and exploring her birth country and talking to fellow adoptees, she said she has not decided whether to try to locate her birth parents or not.

"Some people say there's no harm in filling up the form (to find her birth parents) but I don't know... Some adoptees get no answers even though they have found their birth parents and it's even more frustrating if they are not honest with you," she said.

Ms Huits, who found her father easily through proper records kept in her adoption file, still has no clear idea what happened to her mother, who was separated from her father when she was put up for adoption.

"First they said she died in a car accident. Then they said she committed suicide, but I don't know when," she said.

"Last year, my dad told me that she didn't sign my adoption papers, and I don't know when she found out that I was sent for adoption."

When her parents separated when she was 11/2 years old, her mother had custody of her, but took her to her father after six months.

Her paternal grandfather decided to put her up for adoption while keeping her brother.

"My brother said that if she knew I'd come back to look for them, she'd still be alive today."

While she understands their good intentions, she hopes they would stop sugar-coating the truth.

"It'd be nice to get full closure if I can visit (my mum's) grave, to know how she died and how she lived."

She intends to stay in Seoul for another year, to spend more time with her Korean family, especially her sprightly maternal grandmother who lives on a small island off the west coast.

Working with KoRoot, she hopes to change the way people view adoption, which she calls "legal child trafficking" that thrives out of a demand for children.

The cost of adopting a South Korean child is US$22,500 (S$32,000), according to adoption agency Holt International, which started international adoption from South Korea in 1956.

"Adoption is perceived as such a good thing, but society as a whole should also take responsibility for the life created. Was it really better to take me out of my family? Is there no better system to support the family that keeps the child?" Ms Huits asked.

IMPROVING INFORMATION ACCESS

KoRoot was involved in a recent forum that called for South Korea's adoption law, which was revised in 2012 to tighten control on adoption, to be amended again to make it easier for adoptees to have access to information.

Ms Annie Kim, 27, from Adoptee Solidarity Korea, which advocates alternatives to international adoption, was adopted by an American family and grew up in Sacramento in California. She shared at the forum how she almost did not find her mother.

The tracking code of a copy of a receipt of a telegram from KAS to her mother was blacked out - to protect the identity of the birth mother - but Ms Kim managed to make out the 16 digits by holding the piece of paper against the light. With the code, she was able to get her mother's name and address from the local post office.

One rainy day in July, she drove to the address in Gyeonggi province and her mother opened the door.

"I introduced myself and we both began to cry. It was the strangest feeling... I felt both uncomfortable because the situation was so surreal, and so comforted because she looked so familiar. We sat and talked for a few hours," she said.

Ms Kim has since been in regular contact with her mother, but said KAS called her in September to tell her that there was still no response from her mother.

It turned out that her mother got the telegram, but it had Ms Kim's Korean name wrong.

"Finding our families and knowing our histories shouldn't depend on accidents or luck, when we have the opportunity to fix the Special Adoption Law so that it works better," said Ms Kim.

This article was first published on November 14, 2015.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.