'Motive doesn't matter, so long as people do good'.

Earlier this year, netizens shamed a passenger for yelling at his cabby. Last week, they hit out at a People's Association grassroots leader who allegedly made a vulgar threat against teenager Amos Yee, charged over online rants. Is such tit-for-tat behaviour worrying?

When we are agitated, we can lose our own sense of balance or sensibilities. And when we become vengeful against people who have done wrong, there lies the possibility of committing the same wrong, because we have lost restraint of our own emotions.

It's one thing to point out that something is not right and express our distaste. It's another to mete out our own vindictive justice by behaving in a way similar to, or worse than, what the perpetrator had done.

When people start lynching, it is as if there is no law and order. It becomes dangerous because there is no proper process or constraint. There is danger of causing more harm than good.

It is worrying, of course. As Mahatma Gandhi said: "An eye for an eye will only make the whole world blind."

We must mature as a society and have a deeper sense of dignity in how we express ourselves. We should be able to say something without having to resort to expletives or threats - that just reflects poorly on ourselves.

I don't have a magic bullet. There will always be such people. But it would help if more have the courage to speak up and say it is not necessary to be uncivil.

There was a report this week of a flat in Eunos that was infested with pests due to hoarding, and had plagued neighbours. An HDB survey also showed that while fewer residents were inconvenienced by their neighbours, more of those who were, found it "intolerable". What does this say of the gotong royong (community) spirit?

That case is very sad - people who hoard may have a mental or emotional problem and need help. So I don't think these are necessarily bad neighbours in the sense that they purposely cause trouble for their neighbours.

That said, unlike the kampong days when it was possible to know everybody, now it's impossible.

But I don't think the spirit has totally been destroyed. The Singapore Kindness Movement (SKM) started an initiative called Let's Makan last year to encourage people to get to know their immediate neighbours through sharing food.

We now have more than 2,000 people who have indicated interest.

And we often hear of stories of neighbours helping to take care of plants, pets, and look out for each other, so I won't say the kampong spirit is completely dead.

We just need to be reminded that we have neighbours who are friends-in-waiting, to whom we just need to reach out to be friends and to help one another.

There have been many campaigns urging gracious behaviour on public transport. What does this say about the DNA of Singaporeans that we need these campaigns?

We are human, and so harbour a complex range of different emotions and motivations. Different people conduct themselves differently in different contexts.

If people give up their seats, we would never know what it is that compelled them to do so.

It could be their upbringing, their sense of what is right, a fear of appearing on citizen-journalism website Stomp, a fear of reprisals due to social pressures. Or it could just be because they've been reminded by our campaigns.

It doesn't matter.

For me, I think what it shows is that people do recognise what is the right thing to do. And when they are reminded, they will do it.

We just need to see more people doing the right thing, to create a more pleasant society. Kindness and graciousness are things that people resonate with. Sometimes they forget, but a little nudge and a little reminder will help.

And even with the reminders, people have to do it voluntarily.

There are no such things as "laws" of kindness to be enforced.

Why would people forget to be gracious or kind when it should be intuitive? Is Singapore unique in this sense?

No. The Japanese are considered some of the most gracious people around the world today in terms of social behaviour.

But Japan also has its Small Kindness Movement, which has been around for 52 years. That's a lot older than ours (the SKM was formed in 1997, and its predecessor, the National Courtesy Campaign, in 1979) but they have been doing their campaigning quietly.

On Japanese trains, you still hear announcements reminding people not to use their phone, and so on. This need to be reminded is not unique to Singapore.

I believe that, deep inside all of us, there is innate kindness, which is why people respond to messages of kindness. But for the most part, I must confess that people do put their own interest first, and there is nothing wrong with taking care of ourselves first.

I think people simply need to take a step back from being too absorbed with work or immediate concerns and pay attention to the needs of others around them, too.

For example, during the mourning period over the death of Mr Lee Kuan Yew (on March 23), so much kindness was expressed spontaneously. It was as if it had been "unlocked".

Naysayers claim the motives of some people or companies distributing food or water at that time were for publicity or other gain.

We should always give the benefit of the doubt to people.

So long as the action benefits someone, it is good enough, whatever their motivations are. If we start to question, there will be no end to it.

You are co-founder of the Keep Singapore Clean Movement, and graciousness extends to keeping the environment clean. But an appalling amount of rubbish has been left behind at outdoor concerts and stadiums after major events. Also, do you think the Tray Return Initiative at hawker centres is working?

Picking up after ourselves is a habit and, I suspect, over the years, we have been spoilt. In a sense, we are victims of our own success.

Now, the need to take crockery to the sink, to clean up after yourself, is not as urgent - or even expected - compared to when we didn't have helpers.

But depending on domestic helpers or cleaners in the long term is not sustainable because we're not dealing with the source of the problem - people littering.

If we start to do something about this - by not littering, by picking up litter when we see it and reminding people to do the same, I'm sure that after a period of time there will be no more litter to pick up and no need to employ people to keep the city clean.

It's a more complex problem at hawker centres. We need to impress upon stallowners to get workers to focus more on the cleaning and washing, and encourage customers to return their trays.

Is there a dichotomy between Singaporeans and transient workers, leading to most being housed so far away from estates? Is there a "superiority complex"?

There's always a possibility that self-preservation can lead to pride and elitism. The Not In My Backyard (Nimby) syndrome is a difficult issue.

We are a very small country and people have considerations like property prices, which exacerbates this.

This is real humanity - I believe there is innate kindness in people but, at the same time, we also need to take care of ourselves. The challenge is in striking this balance.

Still, as Singaporeans we need to be more appreciative of our transient workers' contributions, and the least we can do is to say thank you.

The SKM has a Graciousness Index, with this year's results to be unveiled next Tuesday. Indexes of recent years have been low. Were you concerned?

I'm not really worried. The Graciousness Index is more to help us do our job, so that we know what issues need to be addressed.

For example, after results showed that people were giving excuses like "too stressed", "too busy", "no time" to not be gracious, we communicated the slogan "There is always time to make someone's day" as a reminder.

But life is actually a bundle of small things. The fluctuating numbers could be due to reasons such as the economy - when it is doing well and things are wonderful, people will naturally feel better about themselves.

Also, I wouldn't say that Singapore is not a gracious society just because of news reports about an ungracious act. That's not true.

All it takes is for one person to say, for example, that she's pregnant and she was not given a seat - and we overlook the hundreds or thousands who do so each day.

But the impact of an unkind action seems to be remembered much longer than all the kind acts that have been going on. That's just human nature.

How do you walk the talk?

It has always been my faith and my belief that we should love our neighbour, and this gives me great motivation and drive.

As a lawyer in the 1970s, I was already involved in pro bono work. I also took in former convicts as staff at my law firm, way before the Yellow Ribbon Project.

And when I was working in Canada, I involved myself in helping to settle refugees from Cambodia and Vietnam.

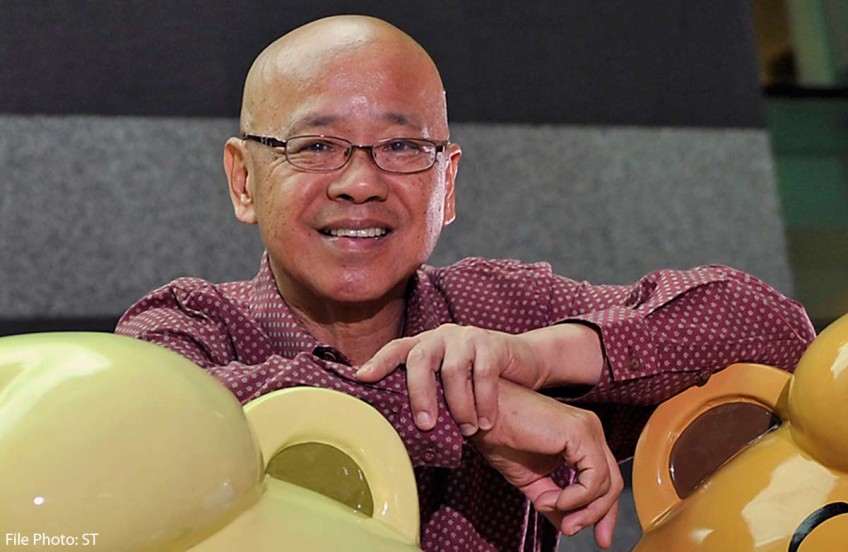

Today, besides being general secretary of the SKM, I'm involved in charity work directly myself, from fund-raising to providing leadership, to getting on the ground and meeting people.

I've also written articles on various emotionally charged issues, like online vigilantism, urging people to think through issues carefully and to exercise self-control. And I've also been attacked for these statements.

But I'm fine with that. I'm sure the articles have resonated with a large swathe of people who elected not to say anything. The silent, moral majority, of course, there will always be.

waltsim@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on May 02, 2015.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.