Innocent lives targeted for maximum impact

Leon Trotsky famously said that even if you are not interested in war, war is interested in you.

The overnight attacks in Paris that have taken 128 lives and counting is testament to the truth of the Russian revolutionary's words.

Ever since the terrorist strike on Mumbai seven years ago this month, which took the lives of 166 people, including a Singaporean lawyer, security experts have braced themselves for the next big strike on a metropolitan city. The issue was not whether there would be another such attack, but when.

Now, they have the answer.

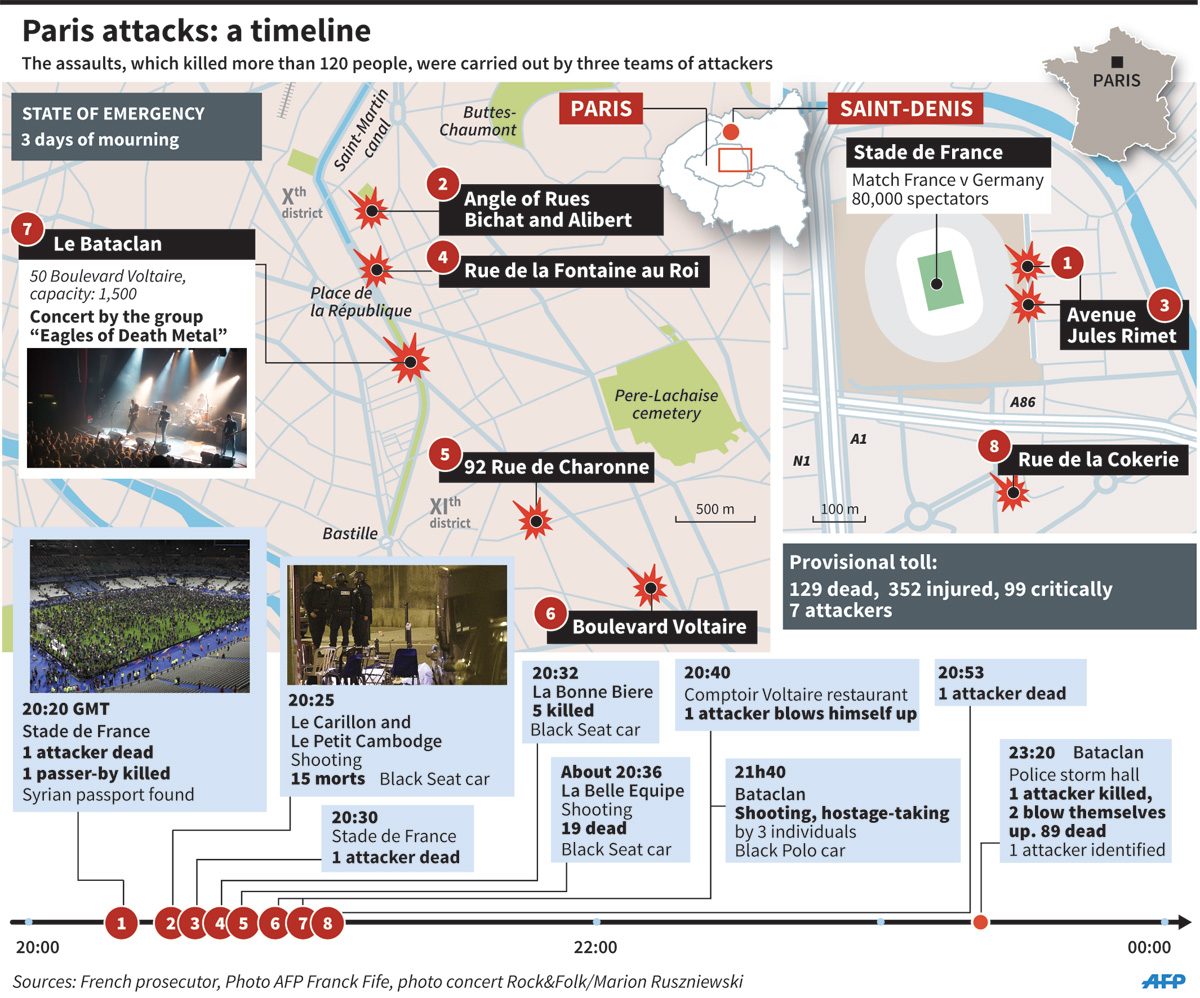

The half a dozen centres that were near simultaneously hit along a 10km stretch from the Belle Equipe bar to the Stade de France, with the Bataclan theatre in between, suggest that the terrorists either emerged from, or gathered in one spot, before beginning their mission. What is not in doubt is that innocent people - with no interest in war and who probably had never heard a gunshot fired in anger - were the target.

That a stadium, a theatre and a crowded restaurant were among the strike points indicate the motives were similar to the Mumbai attack and the one on Bali in 2002 - the saturation coverage that would no doubt follow, thus amplifying the shock from local to global.

Terrorism has changed over the decades. In the 1970s, a cowardly Middle Easterner offered to pack his girlfriend's suitcase, craftily wired a bomb inside, and hand-in- hand walked with her to the check-in counters of Israel's El Al airline to see her off. After the bomb was spotted, nailing the man was easy - the distraught woman, once she realised the extent of her lover's perfidy, told everything she knew about him.

Today's terrorist is not afraid of losing his life, whether out of conviction about his cause or the promise of a steady supply of virgins in the afterlife. Sri Lanka's Tamil Tigers taught women to become suicide bombers.

In Mumbai, the first inkling of the level of preparations that went behind that outrage came from people who reported the attackers jumped out of their boats in pairs, suggesting commando-style training. Likewise, many elements of the Paris attacks suggest expert hands guided the men who carried it out. Until all of them are nailed, the threat cannot be said to have subsided, even as new figures, as yet unknown, rise in the shadows.

While no effort will be spared to run each of the plotters to the ground, it may take years to do so. Dulmatin, the man believed to have set off the Bali car bomb using a mobile phone, was shot and killed by Jakarta police only in March 2009, more than seven years after the event. But, like Osama bin Laden, die they will.

French police, indeed police in every significant metropolitan city, have long prepared for such an outrage. Amid the predictable criticism of lax security will be forgotten the dozens of unsung successes in preventing other attacks, in Paris and elsewhere.

Between preserving the freedom of movement of ordinary people - especially people who value their liberties as much as the French do - and ensuring their safety is no easy task. This was the lesson of the Charlie Hebdo-related murders. Nevertheless, the authorities responsible for homeland security have done their best, whether by monitoring suspicious conversations, installing closed-circuit television in crowded areas and, where necessary, infiltrating crowds.

But the sophistication and determination of the enemy, as well as his ranks, have risen as well. How to stop every touristy type sporting a backpack? That is the dilemma. Big metros, especially one with a swinging night life, are not easy to defend. The assassins know darkness is their friend and the more crowded the place, the bigger the impact of their deeds.

Paris, with its art galleries and cafes where lives are measured out in coffee spoons, embodies the sans souci spirit that the extremists of ISIS so seek to crush.

It is forgotten that France's spirit of tolerance is the reason it has always been host to every kind of refugee - from Iran's Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini to Tamil Tigers to those fleeing from Syria, including possibly, a few planted by ISIS.

Indeed, Voltaire, the 18th century French philosopher after whom one of the streets that witnessed the attacks was named, said as he prepared for death, that he left "not hating my enemies, and detesting superstition". For all these reasons, this will not be the last strike on the city that Ernest Hemingway called A Moveable Feast.

The challenge is to provide extreme vigilance without compromising on freedom of movement and mingling. For, to concede that would be to give up the fight.

This article was first published on Nov 15, 2015.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.