Seeking ayslum in Australia but stuck in Indonesia

JAKARTA- With a view overlooking Mount Salak and a cool breeze blowing, Madam Parveen kneads dough on the floor of the small house in Cisarua district, Bogor.

Sitting next to the 48-year-old, husband Ahmad E-Chashtari, 53, and daughter Nagin, 18, help prepare the dough mix. Her son Saman, 24, slaps a flattened dough paste on a heated stove.

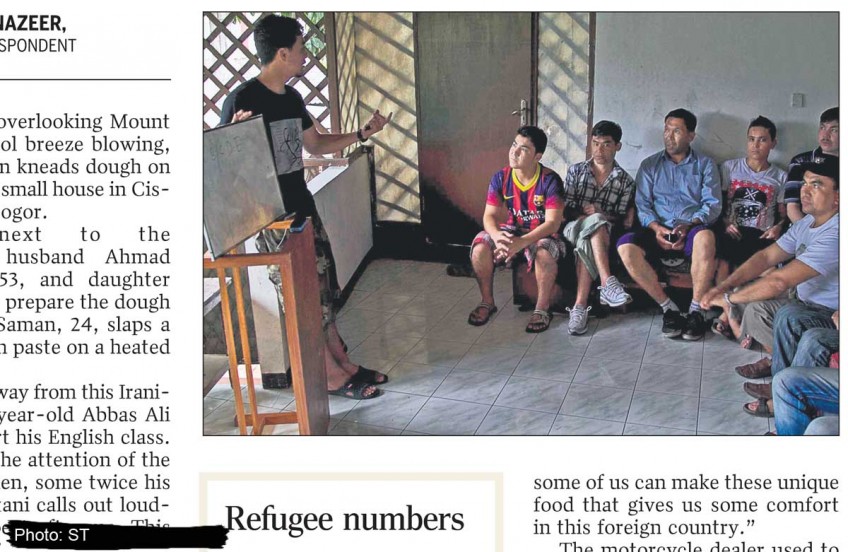

Two units away from this Iranian family, 23-year-old Abbas Ali is about to start his English class. Commanding the attention of the eager grown men, some twice his age, the Pakistani calls out loudly: "Please repeat after me. This is A, this is B."

The idyllic setting and routine activities belie the plight of this expanding community of Australia-bound asylum seekers in limbo in Indonesia as they wait to be granted refugee status. The impatient ones attempt a perilous sea journey to Christmas Island. Some drown, others turn back.

Their future has become even more uncertain and dangerous now that Australia has vowed to turn back asylum-seeker boats to Indonesian waters, sparking a diplomatic row over sovereignty between the two countries exacerbated by recent spats over espionage.

Both communities faced persecution at home and they have bonded as they find acceptance with each other. It is also in this hilly district 75km south of Jakarta, that they have cultivated a micro-economy as they bide their time in an unfamiliar land.

Thousands of asylum seekers are clustered in this district known as "kampung Arab" with its Middle-Eastern food and signs in Arabic, catering to Middle-Eastern tourists flocking there for years for the cool weather and scenery. The location is convenient as it is a short two-hour trip to Jakarta's branch of the UN refugee agency to monitor their refugee application status and cheaper than trying to stay in the capital.

"Let the countries talk politics," says Mr Ahmad in Persian. "We are facing daily challenges - how do we get money to eat? We want to work, but that is forbidden."

His son, Saman, then takes out a steaming crisp Middle-Eastern pita from the stove to be piled with others and wrapped in packs of 10 and sold for 15,000 rupiah (S$1.56).

The family fled Iran after being harassed with death threats for practising Sabian Mandaeism, a 1,800-year-old faith that reveres John the Baptist and considers Abraham, Moses, Muhammad and Jesus false prophets.

The price of their pita is a bargain, earning them just enough to help pay rent. Their buyers are fellow asylum seekers holed up in boarding houses where six or seven people share a room roughly half the size of a Singapore HDB master bedroom.

Some lease small single-storey houses using savings or money remitted by relatives because rentals alone can hit 1.5 million rupiah, not including 900,000 rupiah for food and expenses.

"Earning money this way, cooking for our brothers and sisters here, gives us some dignity," says Mr Ahmad.

Mr Abbas teaches English for free, though another asylum seeker turned teacher charges 100,000 rupiah for 16 lessons a month. "Many are restless doing nothing here," he said. "Teaching them English gives me something meaningful to do, and for them, something new and useful to learn."

Next to the Chashtari family, a fellow Iranian family of five makes "turshi", a vinegar-filled mix of garlic, cucumber, carrots and cauliflower. It goes for 5,000 rupiah a bag the size of a tennis ball, netting the family up to 200,000 rupiah weekly.

"We miss our homes, we miss our food," said Mr Shabbir Hussain, 34, who wears a white T-shirt with the faces of his wife and two children printed in front, and that of his youngest, his 18-month-old daughter, printed on the back. "So we are thankful some of us can make these unique food that gives us some comfort in this foreign country."

The motorcycle dealer used to earn US$1,000 (S$1,267) monthly, but gave it up to pay a people-smuggler for his 10-day journey. That cost him US$10,000 and took him through five countries before reaching Indonesia.

Mr Shuhaib Hussain, 24, who is not related but boards in the same unit next to Mr Shabbir, says: "If we stay, we will die. You won't know when you will be killed, but for sure, you will die."

The computer science graduate fled Pakistan fearing he was being targeted because he belonged to the ethnic Hazara community - one of the most targetted Shi'ite communities in Pakistan. His cousins were shot dead and his family got death threats.

Like many single men there, he is braving the rough sea journey from Indonesia to Australia, where he hopes to be granted asylum before getting his family to join him.

Mr Naqsh Murtaza, an ethnic Hazara and a former broadcast anchor with an Afghan television station, said: "I used to live in a big house, overlooking large agricultural land that we owned.

"I've tried to stay in hope things will change, but since my elder sister was killed, and before that, my great-grandfather, my grandfather and father, we decided it was best to seek asylum."

While most Indonesians accept their presence, some have petitioned for them to leave for fear of social problems. The asylum seekers in this community said another group was told to clear out.

Others have been mistaken for their richer Middle-Eastern tourists and forced to pay more for "ojek" or motorcycle taxi rides.

"We have heard of cases of asylum seekers who get punched by locals, but I am sure those who did, were not behaving," said Mr Naqsh. He admits that they feel like second-class citizens wandering aimlessly.

With tears welling up, he says: "People forget that we left everything, risked our lives and spent nearly all of our savings to get to another country. Why would we go through all that trouble if life is indeed all right in our countries?"

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.