Inside Singapore’s oldest Islamic religious school, where they put faith in Apple iPads

About a thousand years ago, the Muslim world flourished with math, science, medicine, culture and economics.

It’s unrecognisable now, but Baghdad in the 8th to 13th centuries was an intellectual centre, a hub of learning that hosted the greatest collection of knowledge in a grand library known as the House of Wisdom. Muslim scholars gave the world devices that could read the stars, surgical instruments, and algebra, named after the Arabic word “al-jabr”, which translates to the “reunion of broken parts” in English.

But as religious conservatism and fundamentalism slowly took hold, the scientific method was tossed in the trunk, argues Pakistani nuclear physicist Pervez Amirali Hoodbhoy, while regular conflict in the Middle East didn’t exactly help push things forward.

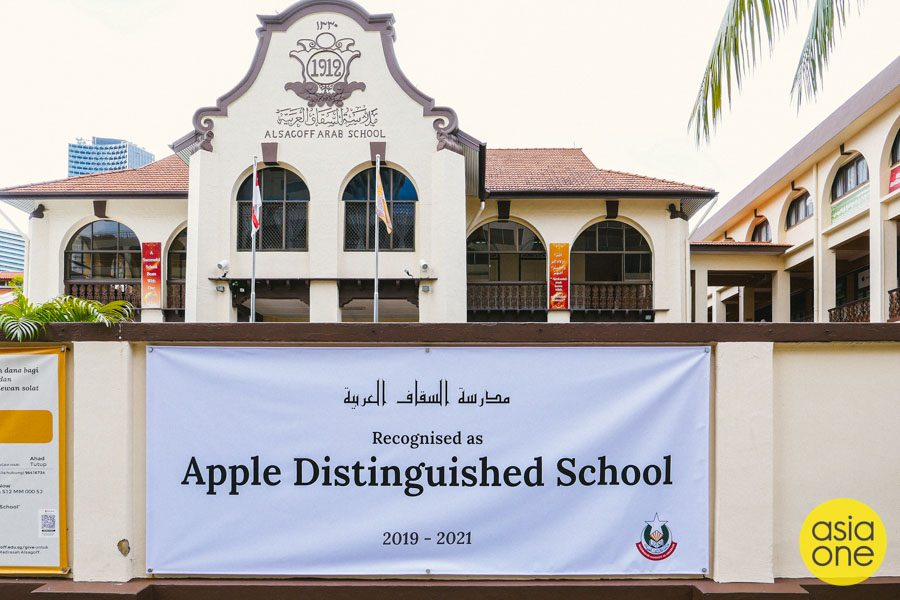

Centuries later and over 7,000 kilometres away from the Middle East, an Islamic institution holds a sturdy belief that a conservative, religious education system doesn’t need to prohibit modern, cutting-edge technology. In fact, quite the opposite: Madrasah Alsagoff Al-Arabiah has fully embraced the cult of Apple — so much so that it has scored the official title of being an Apple Distinguished School. It's a rare title attained by just 400 schools around the world, including Nanyang Girls' High School and Singapore American School.

Located along the Jalan Sultan stretch, the Islamic religious school (one of six on the island) was founded as far back as 1912, an institution established upon the legacy of the last will of successful Arab-Singaporean merchant and philanthropist Syed Mohamed bin Ahmed Alsagoff. As the island’s oldest surviving madrasah, it was gazetted for conservation in 1989.

With that kind of heritage, it wouldn’t be unusual to presume that the school’s curriculum remains rooted in the early 20th century. Were the students are still scrawling on parchment with a quill? Did their education solely revolve around what is taught in the Quran?

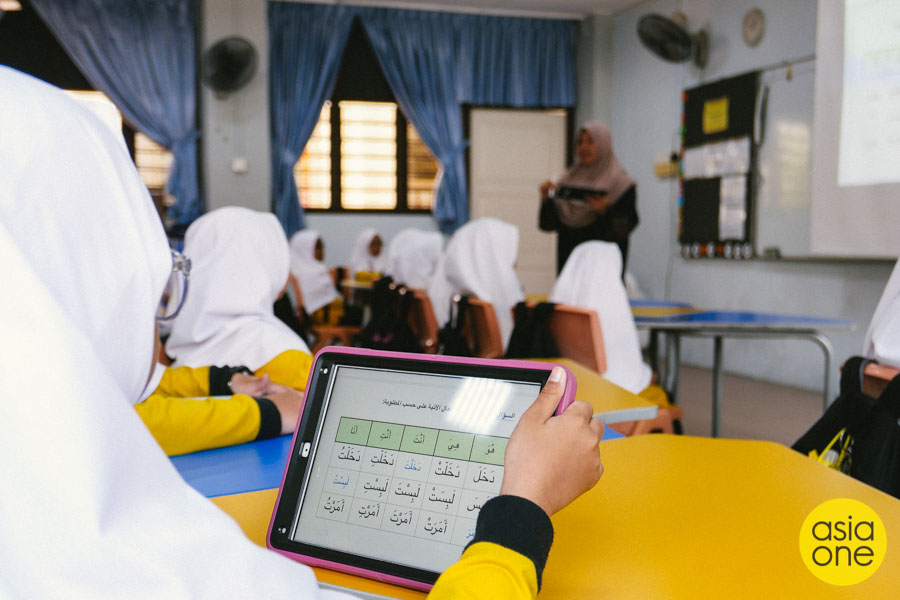

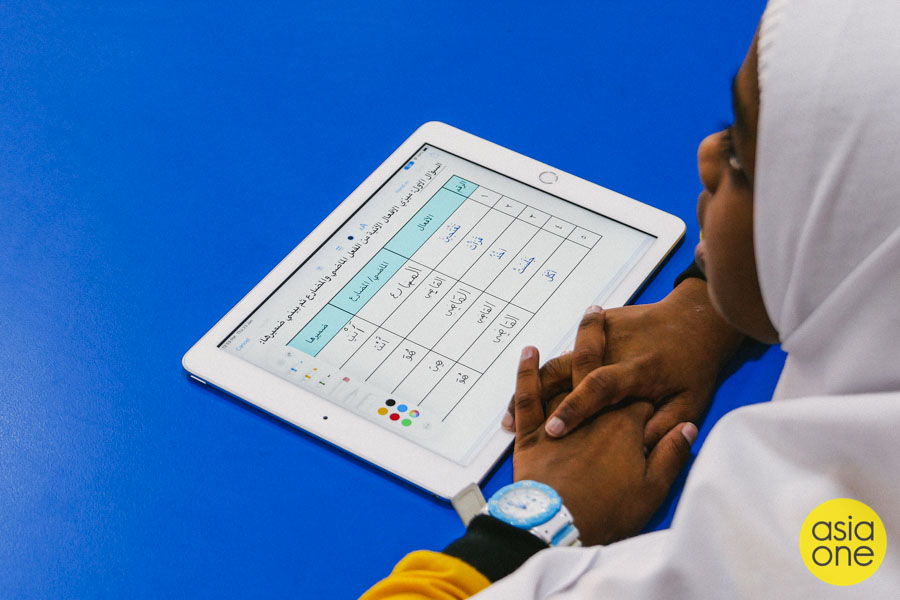

It could not be further from the truth. This is, after all, an institution that has made iPads mandatory for every single enrolled student and everyone in the teaching faculty. Technology is so entrenched in lesson flows that each classroom has an Apple TV console hooked up to a projector, with teachers monitoring their students’ activities via the Classroom iOS app while casting slides, exercises, and completed student works on the screen.

No textbooks needed at all — just iPads of various makes (from the Mini to Pro models) on the tables, with kids as young as 7-years-old navigating the screens with swipes, pinches, and taps like seasoned tech-heads. Teachers were just as proficient balancing their iPads on one hand and their actual tasks on the other, whether it's articulating Arabic phonetics or defining ionic equations.

Who would have thought that future-forward classroom facilities can be found in a 108-year-old Islamic school for girls? Heck, some of our mainstream primary and secondary schools might not even be equipped with proper classroom facilities, much less have teachers who can nimbly navigate Swift Playgrounds to teach basic coding.

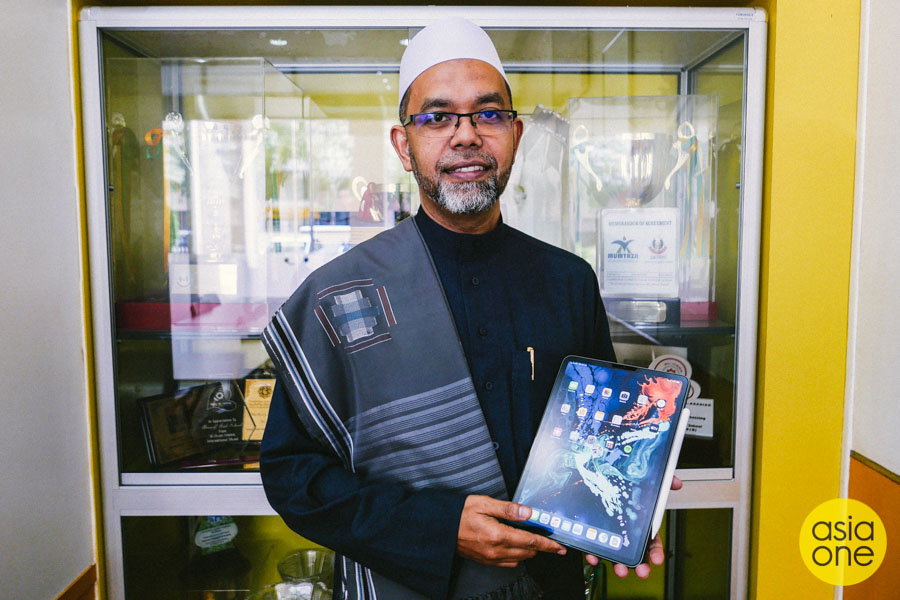

The current principal of Madrasah Alsagoff Al-Arabiah, Ustaz Syed Mustafa Alsagoff, readily admits that he’s a bit of a computer geek. Outfitted in a dark grey thawb, a soft white songkok, and an unwrinkled scarf draped around his shoulder, the Ustaz (the Arabic honorific for teachers) projects a quiet aura of authority despite his zen-like manner (the salt-and-pepper beard helps).

His tool of choice: Apple’s 11-inch model of the 2018 iPad Pro. With an Apple Pencil of course.

Having come on board in 2011 to take over the school’s former custodian Syed Abbas Mohamed Alsagoff, he carried on his predecessor’s vision to dismantle the perception that students who undergo madrasah education are left behind by modernities like technology.

An initial study was conducted internally to find out what device would fit perfectly in classrooms, and at that time, tablet computers were just getting mainstream thanks to Apple unveiling their very first iPad. Despite all the jokes about its name 10 years ago — and skeptical predictions about the popularity of tablets — today’s landscape is positively littered with folks thinking of replacing their laptops with the latest iPad Pro setup.

“When Apple introduced the iPad, (Syed Abbas) purchased the first one and saw his own grandchildren playing with it,” Ustaz Syed Mustaffa recounted.

“He noticed that even small kids could engage with the device, so why not bring it to school?”

And so it was the first generation of iPad devices that the madrasah ordered in bulk. Hundreds of them, in fact, which the school fully sponsored and gave out to its students. It wasn’t even a partnered deal with Apple, Ustaz Syed Abbas recalled; it was something that the school jumped into just to get things going. They weren’t cheap too, so the first wave of students who got their hands on iPads wasn’t allowed to bring the units home.

“From the beginning, we tell the students that these are learning devices — not for entertainment purposes or social networking,” he attested.

In those early days of the iPad, there weren’t that many apps that could actually support a full-fledged educational system, not to mention a specialised curriculum such as Madrasah Alsagoff’s combination of Islamic knowledge, English, Malay, Arabic, Mathematics and Science syllabuses.

So the school embarked on an independent journey to develop its own software and digital learning materials, training its students to digitise textbooks and produce interactive content that could be shared among their peers and future generations. This they did through iBooks Author software — Apple’s e-book writing app — that allowed every student to contribute to the efforts. By the time they reach Primary 6, they would have been taught to create and publish textbooks for younger students to use.

Meanwhile, the teachers are recognised Apple Teachers, meaning all of them are officially trained to work with the iPad on top of other software skills in iWork, iTunes U, and Swift Playgrounds. In other words, these teachers can all code, and can teach coding to students at every level.

The experiment turned out to be a success, and in 2016, the madrasah made it compulsory for every one of their students (or rather, their parents) to purchase iPads for use in school every day as their personal learning device.

Despite the iPad’s popular usage as a portable big screen to watch Netflix or play games, Ustaz Syed Mustaffa made it clear that the tablets are strictly used for education in the school. Which is something that he keeps assuring to parents.

“Instead of using these kinds of devices for entertainment, we are teaching them that these devices are very useful for learning. You can actually have positive screen time.”

Nearly a decade since the madrasah’s big technological venture, parents wanting to enrol their girls into the school know that they’ll have to buy iPads for their kids.

At least two units throughout the course of their education too, the Ustaz reminded, since each new iPad only remains useful for five to six years before needing an upgrade — be it due to Apple ending updates for old models or just the general deterioration of internal hardware. Such is the familiar cycle of life for today’s gizmos that aren’t made to last forever.

Today, the students have their own tablets that they can bring back home to study, revise lessons, or do their homework. It’s a helluva lot lighter as well, when you consider that they don’t have to lug around multiple textbooks like so many of us did.

Come to think of it, it is kinda strange to picture handing powerful tablets to kids and just let the computer be a crucial component of their entire 12-year educational lifespan at the school. Digital addiction is, of course, a very real (and crippling) thing.

It doesn't appear to be the case here. 13-year-old Secondary 1 student Sofiyyah binte Mohd Amirullah tells me that her first year in the madrasah included basic lessons in how to use an iPad, and how they can use it for their lessons. Advanced usage came in the later years, when they would have to complete worksheets and submit audio and video materials to their teachers. At no point were they under the impression that it's for anything else other than for learning.

“The best thing about using the iPad is that when we have a group project, we don’t need to go to our friend’s place because we can use [a feature called] collaboration to work together from home,” she remarked.

“The iPad is useful, but we have to accept certain restrictions to make it a learning device,” offered fellow Secondary 1 student Nurhana binte Rehan. “Our iPads are meant to read e-books, write notes and do homework — we don’t use it to play games or watch YouTube. It’s a learning device for us.”

The absence of a digital divide from the get-go has clearly made a huge impact on the kids, even if they're not going through a mainstream education system. Nurhana expressed her interest in wanting to return to Singapore after graduating from Islamic universities overseas and continue writing e-books for kids to enjoy. Sofiyyah, on the other hand, wants to pursue coding and hopefully build robots, machines and apps.

It’s been a long, unorthodox journey for Ustaz Syed Mustaffa, who has faith that algorithms and electronics don't need to separate from the world of Quranic scriptures and theological values. Madrasah Alsagoff Al-Arabiah getting recognised as an Apple Distinguished School wasn’t even the goal in the first place; he just wanted to craft an engaging learning environment.

In a century-old building that can’t extend or modify its structures (heritage conservation issues and all that jazz), the Ustaz found a different route that works just as well.

“We cannot expand in the physical sense. But if we have all these digital resources that we created by ourselves, we can still expand. Virtually,” he laughs.

ilyas@asiaone.com