TV special unleashed the trauma of Korea's divided families

SEOUL - Thirty years ago, South Korea's state broadcaster KBS decided to help reunite families separated by the chaos of the Korean War, and put together a live TV special with a 95-minute time slot.

The programme ended up over-running; not by hours, days, or even weeks, but by four months.

"Does Anyone Know This Person?" was the title of the special - a seemingly innocuous question that KBS producers hoped might jog a few memories and, maybe, help bring some broken families back together.

What it did was trigger a spontaneous public eruption of pent up longing and trauma that gripped the entire nation like nothing before or since.

Unlike the high-profile family reunion that will be held from Thursday in North Korea, the KBS program was focused not on families divided by North and South, but those inside South Korea who had been separated during the 1950-53 conflict and its turbulent aftermath.

Tens of millions of people were displaced by the sweep of the Korean War which saw the frontline yo-yo from the south of the Korean peninsula to the northern border with China and back again.

Many families found themselves separated in the resulting social chaos that lasted long after the 1953 ceasefire as people focused all their efforts on survival amid the devastation.

The KBS broadcast was aired live on the evening of June 30, 1983.

The format allowed divided family members 15 seconds airtime each to appeal directly to lost relatives - not knowing if they were in the South, or even still alive.

'It just went on, and on'

The response was immediate and overwhelming as the TV station was flooded with thousands of calls from members of the public responding to the appeals or desperate to make their own.

"Back then we were not allowed to broadcast past midnight, but we soon realised that we couldn't simply stop there," recalled one of the show's presenters, Lee Jee-Yeon.

"So we called the Culture Ministry for permission to keep going, which we got," Lee, now 66, told AFP.

"There were people living in the countryside who jumped into cars and taxis and drove to the TV studio in Seoul in the middle of the night.

"I couldn't drink because I had no time to go to the toilet ... it just went on and on," she added.

And on, and on - non-stop for 16 hours, and even after that it was clear there would be no containing the phenomenal response.

KBS ended up airing the program in live spurts for the next 138 days.

By the time it finally finished on November 14, the combined live broadcast time totalled 453 hours and more than 10,000 people had been reunited.

"Until then, we really had no idea that there were so many separated families out there. We were in shock. The wave of emotion was simply incredible," Lee said.

Most South Koreans remember the period vividly, as a sort of collective hysteria broke out, with families and friends cramming together in front of their television sets, weeping at the dramatic scenes unfolding daily in the studio and outside.

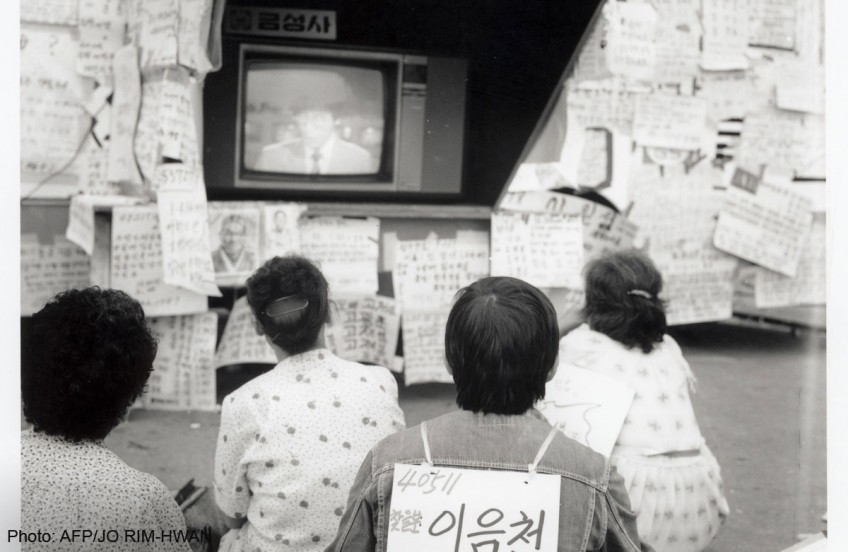

The KBS building was besieged for weeks and the area outside was covered with rough posters bearing desperate hand-written descriptions of lost relatives.

'People would be shouting at their TVs'

Some people covered themselves head-to-toe in similar leaflets, hoping that they might jog a memory for a passer-by or someone watching on TV.

"I was just a teenager at the time and I remember finding it a bit disturbing," said high school teacher Kim Hyeong-Ju, 45.

"My parents were glued to the television and there was a lot of crying, and I'm not sure I really understood what was happening.

"My mother's elder brother had been killed in the war, and she became convinced he might actually be alive and living alone somewhere. My father had to stop her going to the TV station," Kim said.

The live broadcasts would intentionally heighten the drama, by showing potential matches on a split screen before their reunion.

"People would be shouting at their TVs, saying "Yes, they are the ones! They are family!" Lee recalled.

The obvious question, in retrospect, is why it took so long - 30 years - for such an initiative to be launched.

State radio had aired reunion programmes along the same lines before, but they lacked the visual impact of television.

The 1983 special was broadcast shortly after colour television became the norm, and TV ownership had become widespread.

"The timing was right," said Lee.

"Also, you have to remember just how poor most people were in the wake of the war," said Lee.

"Everyone just struggled to eat and survive each day and there was no time or resources to put into looking for families.

"Many thought their relatives were either dead or in the North, and many were separated when they were little kids, so they didn't have a lot of memories to go on," she said.

The cultural impact of the KBS show was significant, and it provided the background to a number of films, plays and books, including the 1985 movie "Gilsotteum" by the noted filmmaker Im Kwon-Taek about a woman searching for her lost son.

For Lee, the drama turned to personal reality when she was reunited with her brother at a North-South family reunion event in 2000.

"In one way, all Koreans are hostages of division," she said.