"What we need is to get the successful to understand that they have a responsibility to help the less fortunate and less able with compassion, to give back to society through financial donations, sharing of their skills and knowledge and spending time to help others do better, and to serve the country," he said.

Get the full story from The Straits Times.

Here is the media statement by Raffles Institution:

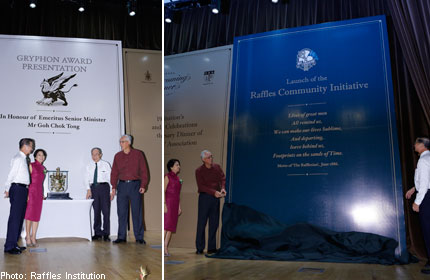

RI honours ESM Mr Goh Chok Tong with the Gryphon award at the Raffles Homecoming 2013

Raffles Institution (RI) presented the Gryphon Award to Emeritus Senior Minister (ESM) Mr Goh Chok Tong at the Raffles Homecoming Dinner, which coincided with the 90th anniversary of the Old Rafflesians' Association's (ORA). The award is in honour of illustrious Rafflesians who had made significant contributions to our community and nation. The first Gryphon Award was given to former Minister Mentor Mr Lee Kuan Yew in 2011.

The Raffles Homecoming Dinner was an event that aimed to renew and reinvigorate the ties that Rafflesians have with their alma mater. The dinner was held in the school hall and was organised as part of the school's 190th anniversary celebrations.

During the dinner, Emeritus Senior Minister Mr Goh Chok Tong also launched the newly-established Raffles Community Initiative (RCI). This Initiative will serve as seed funding for community projects undertaken by RI students, alumni and parents and builds on the Rafflesian tradition of giving back to the community.

The Raffles Homecoming was the first such event since the successful re-integration of Raffles Institution and Raffles Junior College (RJC). The school hopes to expand the school's Raffles Archive and Museum collection in terms of artefacts donated by alumni, and to recognise the central role that RI staff, both past and current, have played in nurturing generations of Rafflesians.

The Homecoming was also an open invitation to alumni to pay tribute to former Rafflesian teachers - to find out how they have been doing and to thank them for all they have done. This is also the first time since the merger of RI and RJC in 2009 that such a largescale gathering of ex-students and their former teachers is taking place.

Here is the full speech by ESM Goh at the dinner:

Professor Cham Tao Soon, Chairman, Raffles Institution Board of Governors Mrs Lim Lai Cheng, Principal, Raffles Institution Mrs Poh Mun See, Principal, Raffles Girls' School Mr Andrew Chua, President, Old Rafflesians' Association Fellow Rafflesians and Friends

Thank you for inviting me to this year's Homecoming Dinner, and for conferring the Gryphon Award on me. I want to dedicate this award to my teachers, my classmates - in particular those in my clique - and the old RI at Bras Basah Road. Without them, I would not have such fond memories of my student days, or be the person I am today. Some of my old classmates are here today (and when I said "old", I really meant old), so let me recognise, or at least try to recognise, a few of them. First, Lee Keow Siong: he was the Head Prefect, school rugger captain and leader of our clique. We grew up together in Pasir Panjang and studied in the same primary school. Next, Cheng Heng Kock: another old friend from Pasir Panjang and our top student. Tan Cheng Bock: the only singer in our group. He stood for the underdog, and still does. Lastly, Lim Jit Poh: a practical and hands-on science student. He organised all our school reunions.

Much has changed since I left RI more than fifty years ago. For example, there is now a school anthem which, sadly, was introduced only after my time. The school itself has twice relocated, regretfully, to many of us. I must confess that I did not feel any nostalgia when I visited the RI at Grange Road and the present school at Bishan. My emotional ties are with the original Bras Basah campus and its surroundings - Capitol Theatre, and the second-hand bookshops along Bras Basah Road; the school field, the old buildings with perpetual flaking paint, school hall with its honour roll of Queen's Scholars, creaking wooden corridors, tuck shops, scout den, prefect's room, and yes, the toilets with their perpetual pungent smell. Indeed, I spent much time in the toilets, not because I enjoyed the aroma, but because I had to supervise boys whom I had sent to clean the toilets for coming to school late. Today, the old RI lives on - in our memories, in a plaque at Raffles City and on the back of our $2 bills. And in case you have not noticed, most of these bills carry the signature of an old Rafflesian! But physical location and appearance changes aside, RI's role in Singapore has not and should not change.

RI as an Inclusive Institution

The RI I grew up in was an inclusive institution. Its students came from primary schools all over. Malays, Indians, Eurasians, Chinese; Muslims, Hindus, Buddhists, Taoists, Christians, free-thinkers; rich, middle-class and poor students: we were all there, rubbing shoulders in and outside the classrooms. RI was indeed a melting pot of Singapore's best male students.

RI helped shape Singapore society through its inclusive meritocracy and secular outlook. Many of its alumni, whose values were ingrained in school, went on to become leaders in the public and private sectors.

But going forward, and as our society matures and stratifies, would RI remain an inclusive meritocratic institution? Or are the seeds of elitism already being planted within its walls?

Evolving Meritocracy in Singapore

At its core, meritocracy is a value system by which advancement in society is based on an individual's ability, performance and achievement, and not on the basis of connections, wealth or family background. For Singapore in particular, a meritocratic system, while not perfect, is the best means to maximise the potential and harness the talents of our people to society's advantage. However, by recognising and rewarding individuals according to their performance and achievement, meritocracy also differentiates and strings out individuals. While unequal outcomes are problematic within each generation, when perpetuated across generations, they lead to inequity.

Levelling the playing field

As a student in RI, I used to cycle 10 kilometres to school from my home in Pasir Panjang. It crossed my mind that the time I spent cycling could be spent studying by those schoolmates whose parents owned cars. Moreover, some of them also had Encyclopaedia Britannica and story books at home. But these students were in the minority. Back then, most RI students came from poor or lower income backgrounds. So, instead of being envious, we were grateful that we qualified for RI on the basis of merit.

My generation's experience was that of an open meritocracy set against the backdrop of a young country on the move. That meant equity and upward social mobility for almost the entire population.

But as our society matured, some stratification became inevitable. Income inequality has grown over the years. Families who had done well are able to give a head start to their children. Ben Bernanke, the Federal Reserve Chairman, called these children lucky. In a speech to this year's Princeton graduates, he reminded them not to underestimate their good fortune and its role in their success. He said, "A meritocracy is a system in which the people who are the luckiest in their health and general endowment; luckiest in terms of family support, encouragement and, probably income; …. and luckiest in so many other ways too difficult to enumerate - these are the folks who reap the largest rewards." So, it is not surprising that many who have not done so well see meritocracy as a system that is biased towards those with better resources, and one which impairs their social mobility.

Our leaders had, in fact, always understood this intergenerational negative consequence of meritocracy. I recall an animated discussion on this topic in 1980, shortly after I joined politics, between then Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew, Dr Albert Winsemius, and Devan Nair. We were sailing down the Yangtze River through the Three Gorges with time to spare. I listened in as they debated issues of income inequality and social mobility, and how to level the playing field for all children. Mr Lee argued that ideally and philosophically, all wealth should revert to the state upon the owner's death. This would ensure that each successive generation would start on an equal footing, without the benefit of inherited wealth. Then each person's success would depend purely on his own hard work and ability. The others agreed that this would be equitable for each new generation, but also pointed out that the idea was impractical.

To equalise opportunities in a practical way, the government has progressively built up the education system, put more resources into all schools, upgraded ITEs and Polytechnics and expanded university places. It is now developing the pre-school education system for those who cannot afford the expensive privately-run pre-schools. These, together with our progressive tax system, the financial support, bursaries and grants we provide to needy students, are part of the government's on-going efforts to level the playing field as much as possible. This is important to ensure that meritocracy remains accepted as a core pillar of our values and that it also benefits those who do not come from well-to-do families.

Guarding against elitism

As parents, we all want our children to have the best possible preparation and head start in life. This is natural and commendable. But when society's brightest and most able think that they made good because they are inherently superior and entitled to their success; when they do not credit their good fortune also to birth and circumstance; when economic inequality gives rise to social immobility and a growing social distance between the winners of meritocracy and the masses; and when the winners seek to cement their membership of a social class that is distinct from, exclusive, and not representative of Singapore society - that is elitism. And we need to guard against elitism, whether in our schools, public institutions, or in society at large, because it threatens to divide the inclusive society that we seek to build.

The practice of meritocracy must therefore not exacerbate the divide between the successful and the rest of society. Meritocracy, taken to a selfish extreme, could result in what is termed "crab mentality". This refers to the situation where crabs in a basket try and climb over each other to get out, while other crabs try and drag down those above them. Such a situation would break down the political and social structure which has enabled Singapore to succeed.

My point is, we must adapt and strengthen our practice of meritocracy to ensure that it continues to benefit the whole of society, and not just those who are bright and able. The solution is not to hold back the able or pull down those who have succeeded. Nor is it to replace meritocracy with another system - there is no better and fairer alternative. What we need is to get the successful to understand that they have a responsibility to help the less fortunate and less able with compassion, to give back to society through financial donations, sharing of their skills and knowledge and spending time to help others do better, and to serve the country. The government will also have to continue to intervene through policies and programmes to give a leg up to the next generation whose families have fallen behind economically. Together, these efforts will ensure that our brand of meritocracy remains compassionate, that it is fair and inclusive for all - not just those who are lucky in their backgrounds or genetic endowments. Advancing Compassionate Meritocracy

Our top schools, including RI, must play a key role in ensuring that elitism and a sense of entitlement do not creep into the minds of their students. Those of us who have benefited disproportionately from society's investment in us owe the most to society, particularly to those who may not have had access to the same opportunities. We owe a debt to make lives better for all, and not just for ourselves. Rafflesians should lead the way as exemplars of the virtues of meritocracy, and help reinforce social inclusion, compassion, and equity in Singapore. 16 In this context, the establishment of the Raffles Community Initiative (RCI) is timely. The RCI seeks to ensure that current and future Rafflesians continue to uphold the tradition of service that the school holds dear. The school's objective is for all students to be involved in at least one sustained community project throughout their years in RI. I hope the RCI will spur even more Rafflesians to see it as their responsibility to improve on what they had inherited.

Auspicium Melioris Aevi.