Seaside confidante

SINGAPORE - Changi Beach greets me the way an old friend does on our latest encounter - picking up just where we left off.

It has been at least four years since I last visited the beach, a childhood playground for my two now grown-up sisters and me. But the soft sand and coconut trees, lanky and bent with age and which line the 3km of shoreline, look the same as ever.

I am visiting the beach with my parents over two weekends to uncover memories over three generations and five decades.

Changi has borne witness to many family events - my mother's childhood spent playing amid the trees of her house just across the beach; the first encounter between my then 21-year-old mother and the man she was to marry, my father; countless weekends with my sisters, building sandcastles and running towards the waves, then scrambling away, giggling.

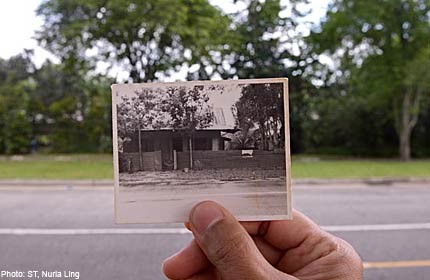

We drive slowly past the roundabout along Nicoll Drive, which is close to the house my mother used to live in as a child, back in the 1960s and 1970s. Shrubs and trees now cover the area where the 2,500 sq ft house once stood.

My grandfather, Mohamed Aly Moideen, a British Royal Air Force driver, pooled his humble savings to buy the single-storey house made of stone, zinc and wood for his young wife and six children in the late 50s.

But he did not live to see them grow up in it, dying of a heart attack at 42. His departure left my grandmother, Habsah Abdul Rahman, then only 29, to raise the children and run the household, a feat she pulled off successfully all on her own.

My mother, Hamidah Aly, now 52, recalls that while her family could not afford luxurious toys, they found many ways to have fun, making use of what they had around them. They were surrounded by 22 coconut trees, 20 soursop trees and a sprinkling of rambutan, palm and drumstick trees, each planted by my grandfather years before, and which provided a forested enclave for playing hide and seek, tree-climbing and observing the noisy chickens at the coop my grandmother kept.

Deftly de-husking coconuts from the trees around her house, my nifty grandmother would give my mother the kernels to use as bowls for masak-masak, the pretend-play game of cooking that she would play with her two sisters.

Ingredients comprised leaves from the trees and fish caught from the river behind the house. My mother remembers that even the cats refused to eat these culinary creations.

Another time, my grandmother painstakingly hammered an iron nail into an old milk can before placing a large candle in it for my mother to play with at night. Till today, my mother remembers the soft shadows and the gentle glow of the lantern.

The clear skies and waters of Changi Beach became a classroom of sorts - the clouds posed a test in deciphering the shapes of animals, and the waters taught the art of pronouncing the various English and European names of ships that went past.

Changi's sandy shores were also the setting of another thrilling game - treasure-hunting. As the waves rolled in, my uncle, the only son in the family, would quickly search the waters for "gold" that glistened in the sunlight - in reality, coins that had fallen out of the pockets of swimmers.

Even when my mother moved with her mother and siblings to an HDB flat at Chai Chee at the age of 11, she did not forsake the beach. As a teenager, it was the go-to destination for her and her friends, the trees providing shade as they listened to stories shared among confidantes. As she grew into a young woman, it would also bear witness to her first encounter with her future spouse.

In 1982, my mum's good friend asked her along on a group outing. The date had been arranged to pair up a friend with another acquaintance, then 30-year-old Mokhtar Amin. The group of six met outside The Cathay cinema before adjourning to Changi Beach in the evening.

As it turned out, it was my mother who hit it off with Mokhtar Amin. She recalls them both pointing to a salt bottle at their dinner table, in reference to a superstition they had read of throwing salt over one's shoulder to get rid of bad luck.

They would also learn that evening that they lived just a block away from each other in Chai Chee.

The beach remained a personal favourite for them on outings and for years after they married in 1985. They would pass on this fondness for the beach to their three daughters.

As I walk on the sand on my visit that weekend, my parents take a rest and sit on a fallen tree trunk on the shore as planes soar overhead.

My mother then tells me how she would dress us in bright colours to spot us easily from afar as we played, and I remember the plastic pails and shovels, my tools of trade almost every weekend growing up.

The homemade egg sandwiches, potato chips and $1 ice cream slices were fuel that energised us through a hard day's "work" of sandcastle- building and seashell-collecting. My parents say they took us there so frequently to give us a sense of playing freely - beyond the walls of our then five-room flat in Ubi Avenue. They wanted us close to nature, just as they had been growing up. We would stay in the sun for hours, having short rests in the shade before taking a dip in the sea, devouring curry puffs afterwards.

My father throws a pebble and I watch it hop on the surface of the water. I remember him teaching us how to do this, though I never quite mastered the art. Yet these experiences were a formative part of our childhood, and perhaps helped define us.

Like our parents, we share a dislike for crowds and confined spaces, and retain a soft spot for the beach and its sea, sand and skies.

As we grew older, work, friends and other commitments took us away from weekends at the beach.

We had also moved to Marine Parade and subsequently Tampines, and headed instead to East Coast Park whenever we needed a quick beach fix.

As a veil of darkness slowly descends, we make our way back to the car.

Waves brush gently against the shore. Other families are starting up their barbecues, the young ones enjoying a last dip in the waters.

Another car pulls in, ready to take our spot. But a friendship this old can hardly be replaced, and as we depart, the leaves merely rustle gently, for proper goodbyes are never needed between old friends.

maryamm@sph.com.sg

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.