S. Africa's Boris the BabyBot opens children's eyes to digital privacy

When Boris the BabyBot, a red robot with long wiggly arms who tracks and profiles babies for The Factory, meets a baby who's too messy to be tracked, the book's young readers join the droid in exploring questions about data privacy.

Boris beeps as he scans babies' smiles and fingerprints and notes their liking for puppies, while adults in white coats monitor the action on their clipboards, in the illustrated story by South African digital rights activist Murray Hunter.

"It is not meant to teach a particular lesson to children about data collection, but rather start the conversation rooted in joy, play and delight, rather than a sense of dread," Hunter told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

"This book creates a visual and narrative point of reference to help a child imagine what data collection looks like," said Hunter, who believes it is the world's first children's book about the secret world of corporate surveillance.

Across the globe, digital rights groups are pushing for the protection of individuals' data privacy.

Unlike in Europe and the United States, where data-privacy laws provide a level of protection to consumers, many Africans have little or no recourse if a data breach occurs because legal and regulatory safeguards often do not exist.

South Africa is one of the few countries on the continent to have a data protection law, passed in 2013, but it is "gathering dust" as it has not been enforced, said Hunter who previously worked with Right2Know, a local freedom of information group.

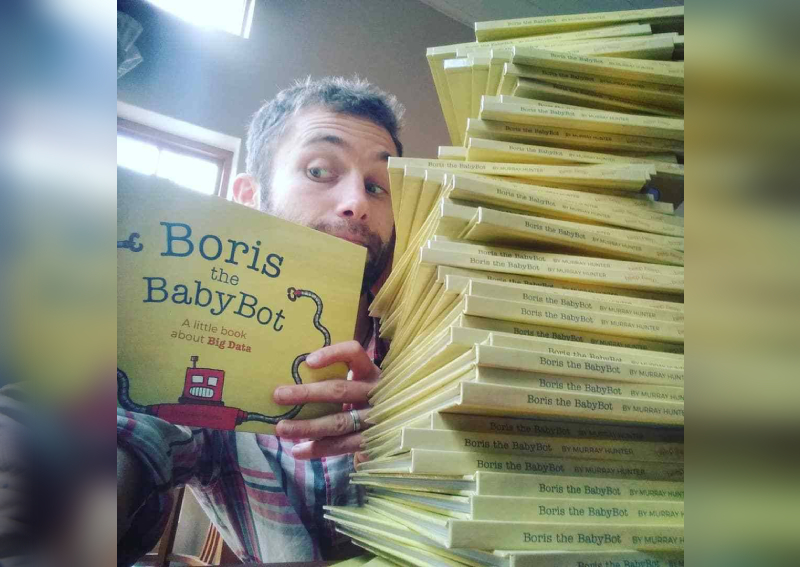

"Major industries such as private security companies, the financial sector and insurance companies are writing the rules for themselves," said Hunter, who raised 60,000 rand (S$5,700) in six days via online crowdfunding to self-publish the book.

"Apparently this is a book a lot of people felt was waiting to be written," said Hunter, whose inspiration for the book, published this month, came from reading stories to younger cousins and friends' children.

Africa, which has clocked the world's fastest growth in Internet use over the past decade, is a growing market for firms like Facebook, which has introduced a Free Basics service accessing some sites in exchange for users providing some data.

"Awareness around children's privacy rights builds knowledge and resilience for their future digital privacy as adults," said Karabo Rajuili, advocacy coordinator with South Africa's amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism.

After queries about whether Boris the robot was named after British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, Hunter decided to donate 50 per cent of proceeds from UK sales to a food bank in Johnson's constituency. Hunter insists the name choice was unintentional.