Hitting all the high notes

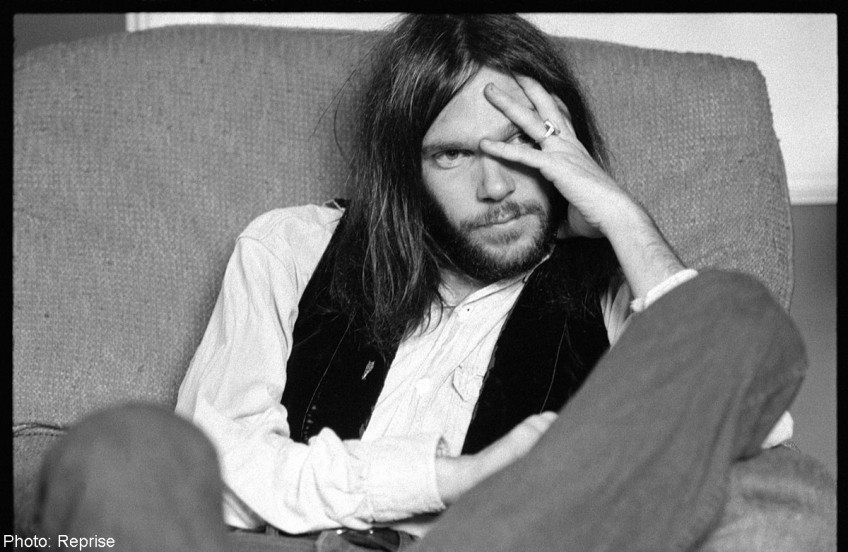

Imagine Neil Young, 24, unknown. Then watch the long-maned Canadian amble into an audition of American Idol and start mewling.

One hesitates to hear how the comely trio of American Idol judges - Jennifer Lopez, Keith Urban and Harry Connick, Jr - would make of the guy's singing voice.

High-pitched, airless as if poultry were being culled, or at least, a lamb shrieking.

Flipping between an alto and a high tenor, it's far from a manly burr.

Certainly, that voice comes to fore in his performances at the Cellar Door in Washington DC in 1970, when he was in fact 24.

Recorded months before the legendary Massey Hall gig in Toronto in January 1971, the Cellar Door songs show how stealthily his voice works its charm on its audience. To a captive crowd, he sings his song narratives with that wheeze.

"Sometimes I feel like a helpless child/Sometimes I feel like a king," he purrs in the last track, Flying On The Ground Is Wrong.

The lyrics - about the disparity between hippies and squares in the wake of the Vietnam War - are apt, reflecting the odd strength in his vulnerability.

Young's voice is riveting as it never loses its sanguine wonder, even when one's knocked down.

He banters with the crowd and pounds on the ivories for some horror-movie effect, quipping: "You'd laugh too, y'know, if this was what you did for a living."

He reaches out, not with the prowess of one's note-perfect singing, but with heart.

He strums his guitar and delivers a "new song" from his album After The Gold Rush called Only Love Can Break Your Heart, supposedly penned for

Graham Nash after the latter split from Joni Mitchell. Sung so softly, it slays.

Another song, Expecting To Fly, soars, his voice entering the ether, as he attacks the piano towards the end. You gasp.

One has the same out-of-body experience listening to Linda Perhacs' second album, The Soul Of All Natural Things - which comes 44 years after her influential 1970 debut, Parallelograms.

Like another reclusive psych-folk icon, Vashti Bunyan, Perhacs has an ethereal mezzo-soprano that beseeches.

It floats high, seeking humanity, not just facile emotions. Sure, the voice, ravaged by age, isn't as pristine as before, but the intent is unsullied.

Contemporary admirers such as experimental musicians Julia Holter and Nite Jewel's Ramona Gonzalez contribute to the album, bolstering the openess with nylon-stringed guitars, subtle electronics, strings and hymnal chants.

It doesn't matter if you buy into the spiritualism of Prisms Of Glass and Song Of The Planets, she stills the air, and you're hooked.

No wonder she counts acts as diverse as Daft Punk, Devendra Banhart and Swedish heavy metal rockers Opeth among her fans.

Folk siren Marissa Nadler may one day achieve the cult status that Perhacs enjoys.

The Boston-based songstress sings in a bell-clear soprano, but there's smoke and shadow behind it.

In July, her sixth and best record, the listener is disarmed by a lustrous purr you can't quite date or place. Is she a Victorian ghost? Or a space goddess?

Her timelessness beguiles. A gem like Dead City Emily illustrates her ability to lull while delivering the chills.

"I was coming apart these days," she promises, an angelic spectre over a braiding of buttery guitars and reverb echoes.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.