What will happen to airfares after Covid-19?

With Covid-19 showing no signs of abating, it seems awfully hubristic to think about travel.

And yet, we have to believe that sooner or later, the pandemic will be brought under control. When that happens, flying will once again be possible. And the question would invariably be: What can we expect to happen to airfares?

On one hand, it seems intuitive that airlines will have to engage in major price wars to coax nervous passengers back to the skies.

On the other, it’s possible that social distancing and other regulations will limit the ability to pack passengers into planes, resulting in an increase in unit costs and, hence, airfares.

While no one knows the answer for sure, here are some of the factors that will influence the final outcome.

Experts predict it could be two years after Covid-19 that crowds at airports return to normal.

Even after borders open up and travel restrictions are lifted, it’s a safe bet that not everyone’s going to rush out to travel straight away. Covid-19 will leave some long-lasting scars, and many may adopt a wait-and-see approach before venturing abroad.

According to San Francisco-based think-tank Atmosphere Research Group, the recovery timeline will stretch out two full years after Covid-19 is declared as being under control.

Weak demand and overcapacity will depress prices, as airlines will generally be trying to bring aircraft back into service to avoid the fixed costs of storage.

Who remembers the day when oil prices went negative ? This phenomenon occurred because demand had dried up to the extent that producers had to pay buyers to take the commodity off their hands and store it.

Prices have since recovered to a more sane US$25 (S$35) level, but that’s well below where they were a year ago.

[[nid:488912]]

Theoretically, this should be a boon for airlines. The IATA estimates that airlines spent US$188 billion on jet fuel in 2019, at an average price of US$65. If the oil market remains soft for the rest of the year, the savings could be very substantial indeed.

However, it’s important to remember that lower oil prices may not benefit airlines if they’ve hedged themselves at much higher prices. Singapore Airlines just announced an extraordinary $710 million loss on fuel hedges, no doubt spurred by the collapsing oil market.

In such cases, airlines are less able to price cheaper oil into their tickets because they’re committed to buying it at more expensive prices.

Although blocking the middle seat doesn’t actually provide the level of social distancing recommended by health experts (the average seat is 45 cm wide, versus the recommended two-meter distance), it does provide psychological reassurance to jittery flyers.

As such, carriers like Alaska Airlines , Delta and Japan Airlines have taken to blocking the middle seats on their aircraft, guaranteeing that all passengers will have an empty seat next to them.

Sample seat map from Japan Airlines showing social distancing- black seats are unavailable.

This is currently feasible because load factors (the number of passengers on a plane, divided by the plane’s capacity) are low, so the opportunity cost of blocking an empty seat is close to zero.

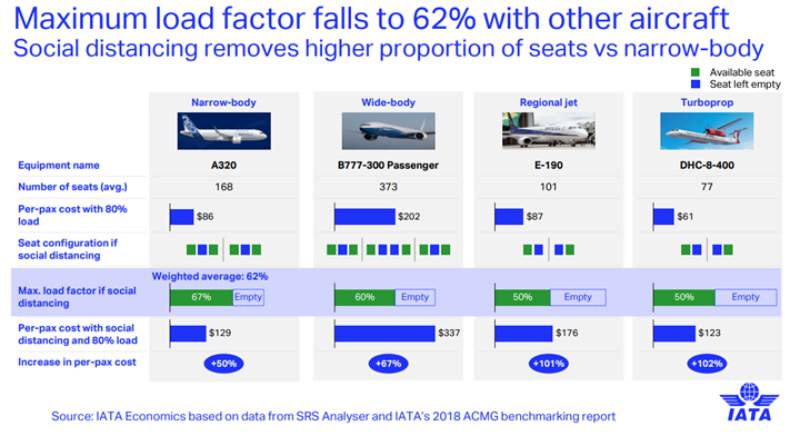

But that won’t be sustainable for long. Blocking the middle seat means an average load factor of 62per cent, which is well below the industry-average breakeven load factor of 77per cent.

For airlines to make a profit at a load factor of 62per cent, the International Air Transport Association (IATA) calculates that airfares would have to increase by as much as 54per cent!

The picture gets worse if ‘true’ social distancing were implemented. According to the BBC , true social distancing would only allow the seating of four passengers for every 26 seats, resulting in a load factor of just 15per cent. Needless to say, the sheer economics of that make it a thought exercise at best.

Before Covid-19, aircraft cleaning could be rather hit and miss. While cleaning crews no doubt work as hard as they can, they’re handicapped by the amount of time allocated.

[[nid:488225]]

That’s because airlines live and die on utilisation — a plane sitting on the ground makes them no money. Hence the obsession with the 30-minute turnaround . Planes are emptied and given a cursory clean, filled and sent back to the skies, all within 30 minutes.

A cursory clean is just not good enough for the new environment we find ourselves in, and we could see regulation mandating minimum turnaround times to allow cleaning crews to do a proper disinfection.

The flip side is that this will reduce the number of flights airlines can operate, and potentially increase the cost of tickets.

Singapore Airlines used to service Las Vegas, once upon a long time ago. SARS put an end to that.

Covid-19 has forced airlines to rethink their route networks, and destinations, which were marginally profitable to serve before the crisis may no longer be so. This means we’re likely to see consolidation, which results in less competition on certain routes and potentially higher fares.

We saw this previously during the SARS crisis where Singapore Airlines cut service to destinations like Brussels, Las Vegas, Madrid, Montreal and Vienna. Many of these routes never returned.

As the first country to go through the Covid-19 pandemic, China was also the first to end it, and with travel restrictions lifted, passengers once more took to the skies.

The IATA’s data shows that average domestic fares fell by 40per cent, from US$143 prior to the lockdown to US$84 after. What is unclear is how much of this was the result of airlines passing on government subsidies and rebates to consumers, and how much was market-driven.

It’s also unclear whether this experience will be relevant to us in Singapore, given how we have no domestic market to speak of, and the dynamics of flight pricing for the international market can be very different.

Assuming that onboard social distancing does not become a regulatory requirement (and given what it would mean for the airline industry, it’s hard to see it happening), I suspect we’ll see initially lower airfares when markets open up again.

[[nid:487530]]

The need to fill seats and the fact that low cost carriers are likely to bring capacity back faster than full service airlines will put downwards pressure on prices.

In the medium term, however, it’s possible that the consolidation caused by Covid-19 will lead to reduced competition and higher fares on certain routes. This is more a concern for flights between less popular destinations (Singapore to Bangkok or Singapore to Bali should remain fairly competitive), however.

In the long run, once the industry fully recovers, it’s likely we’ll see these higher fares get moderated as new entrants once again take the (possibly, foolhardy) step of entering the airline market.

As always, flexibility is your greatest ally when shopping for airfares. If you’re not fussy about where or when you fly, features like Kayak Explore or promo codes on Klook (if applicable) can help you find dates and destinations to fit any budget.

For the latest updates on the coronavirus, visit here.

This article was first published in SingSaver.com.sg.