Freehold versus leasehold landed property: Is leasehold really all that bad?

In previous articles, we've found that freehold status may not help as much as we think with condos. But when it comes to landed properties, it's a whole different ball game. Looking at the performance of leasehold versus freehold landed, we can see it's very distinct from the condo market. Here's what we found:

Note: For the following, we have excluded strata-landed property. This means we've excluded the odd villa, terrace house, or bungalow that's sometimes part of a condo development. We have also kept to leasehold homes with 99 to 103-year leases.

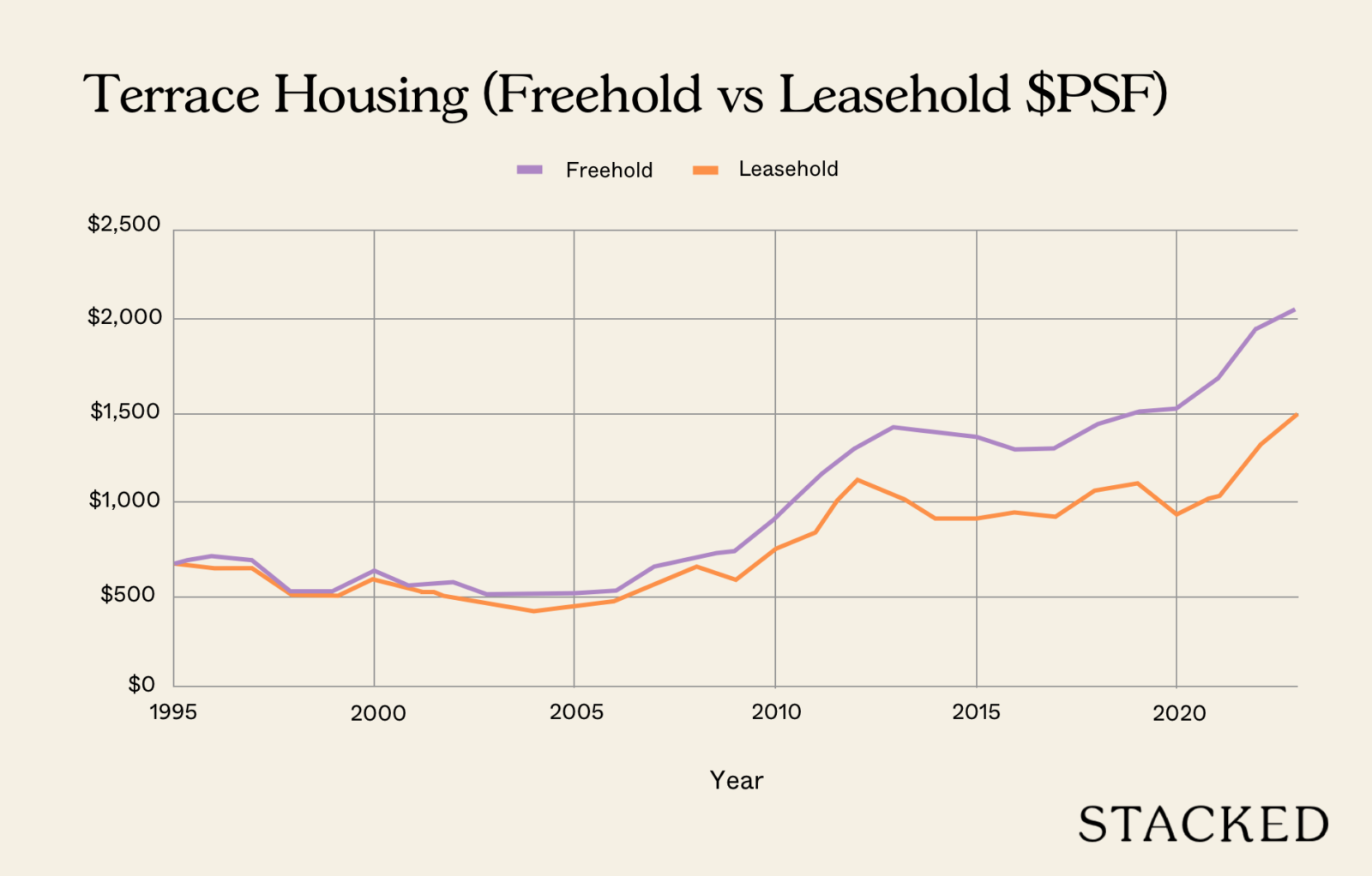

Notice that, right up till around 2003, leasehold and freehold landed prices seemed to move downward in tandem.

This was due to the property market slump at the time: following the Asian Financial Crisis, home prices plummeted around 38 per cent from a previous peak in 1996. In the recovery and run-up to the next crisis however (the Global Financial Crisis in 2008/9), it seems clear that landed property had cemented its reputation as a safe haven asset.

Notice that landed prices generally rose even during the crisis period; and during this time, the gap between leasehold and freehold landed notably widened. As of 2023, it's generally true that freehold landed has significantly outperformed its leasehold counterpart.

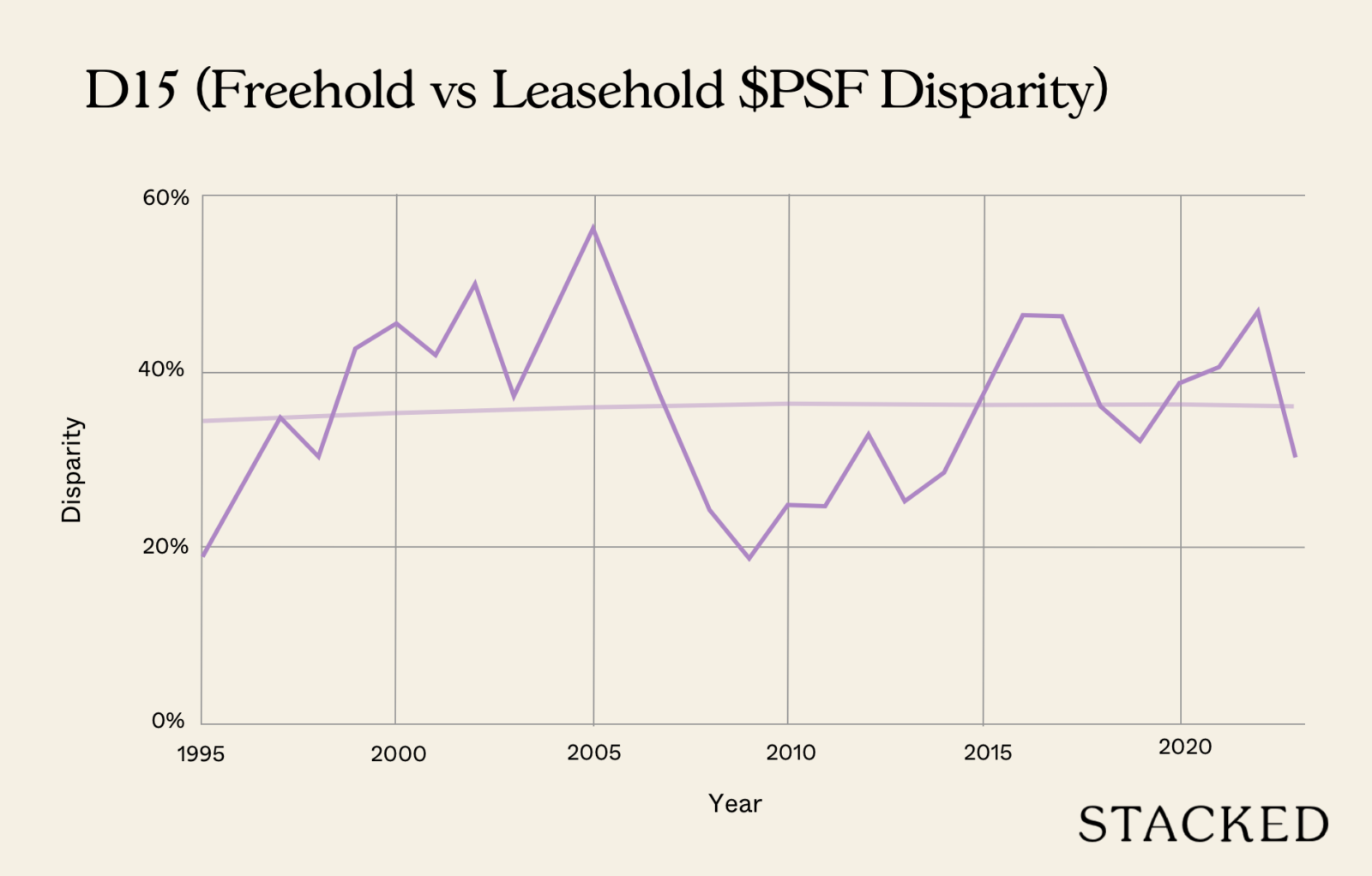

Now here's a chart that shows you the disparity between leasehold and freehold:

As you can see, there's a pretty telling trend here albeit the volatility in the late 2010s. The trendline here shows that the difference in $PSF between freehold and leasehld has widened over time to an even greater magnitude later on compared to earlier years.

Developers are less likely to buy up small leasehold landed plots, because the limited land area restricts the number of units they can build.

Also, most leasehold landed plots are not in prime areas, and are far from public transport. This limits the potential for mass-market condos, which are better suited to these fringe regions.

Moreover, certain landed enclaves are restricted by other types of controls, such as being designated a mixed landed-housing area that's up to 3-storeys high. This helps to protect the neighbourhood characteristics that helps prevent a tall eyesore of a building building sprouting out of the low-density areas.

This is quite different from the condo market, where both freehold and leasehold condos may be redeveloped in as little as 20+ years (usually to the detriment of the freehold condo, as not enough time would have passed for its freehold status to justify its price premium).

As such, the relationship between leasehold and freehold landed is very different from what we see between leasehold and freehold condos.

You'll notice that the disparity seems very volatile. That's because we took into account all landed homes. So let's filter down to just Terrace homes. Why Terrace homes? Because they have the largest number of transactions - especially when it comes down to leasehold landed homes.

Here's what their prices look like:

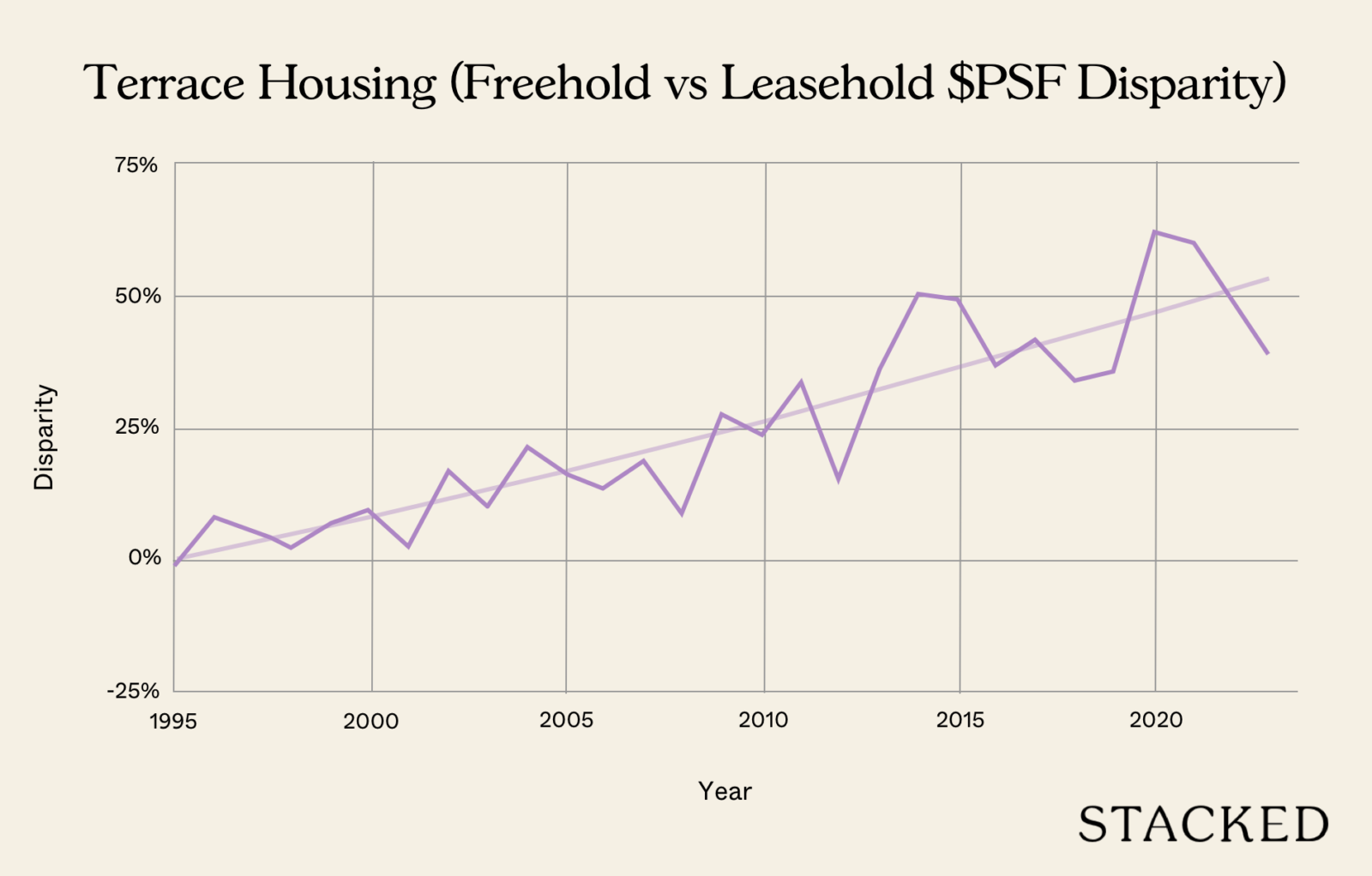

Now here's the disparity in $PSF:

The results show less disparity now, but the end result is similar: leasehold landed properties steadily fall further from freehold counterparts over time.

At the risk of being too specific, we also looked at only landed transactions around Pasir Ris Beach Park. This location was picked because it had the highest number of leasehold and freehold landed transactions:

This is what the disparity looks like:

Again, we're led to the same conclusion. Leasehold landed values drop steadily over time, and fare worse than freehold counterparts the longer you wait. So if we had to make a general conclusion, we'd say leasehold landed isn't a great long-term investment; not compared to a freehold landed home.

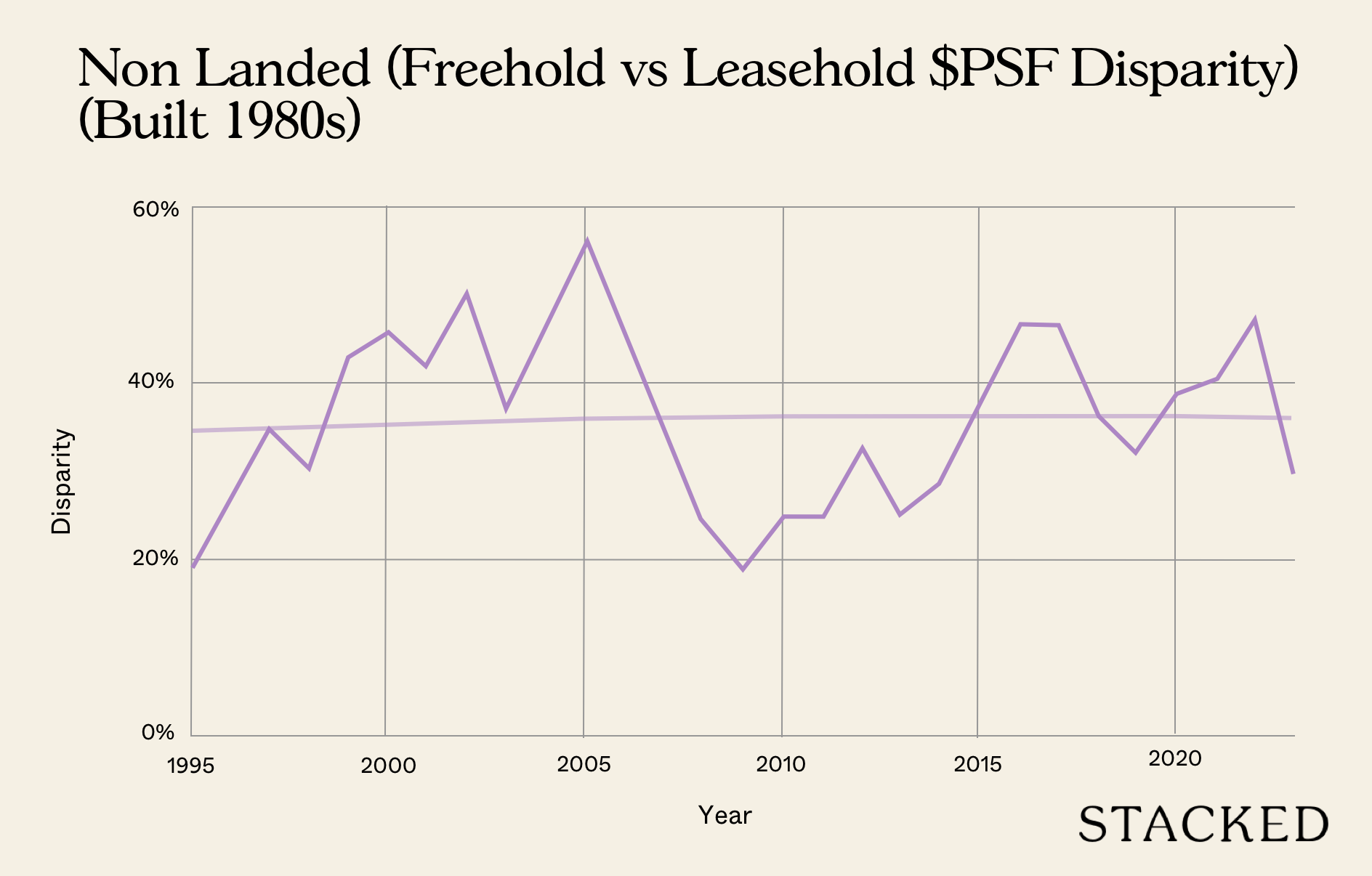

For the following, we will use developments built in the 1980s. This is partly because older developments have had more time to show the effects of lease decay; but also because we don't want to skew the results too much with the effect of newer properties:

The pattern is less distinct, compared to the landed segment. You can see that it's really just sideways. But this may be due to a lack of freehold condos and leasehold transactions within the same location. So as an alternative, we could look perhaps at Orchard Court (built in 1973).

This is one of the rare projects where there's a mix of both leasehold and freehold units in the same development:

The transaction volume is low, so prices are quite volatile. But in general, we can see that in this project, prices for leasehold have been catching up to freehold counterparts. This is quite surprising when you consider that around half the lease is gone; we would have expected leasehold units to have fallen far behind their freehold units.

(This may, however, be due to factors like en-bloc prospects being factored into the price.)

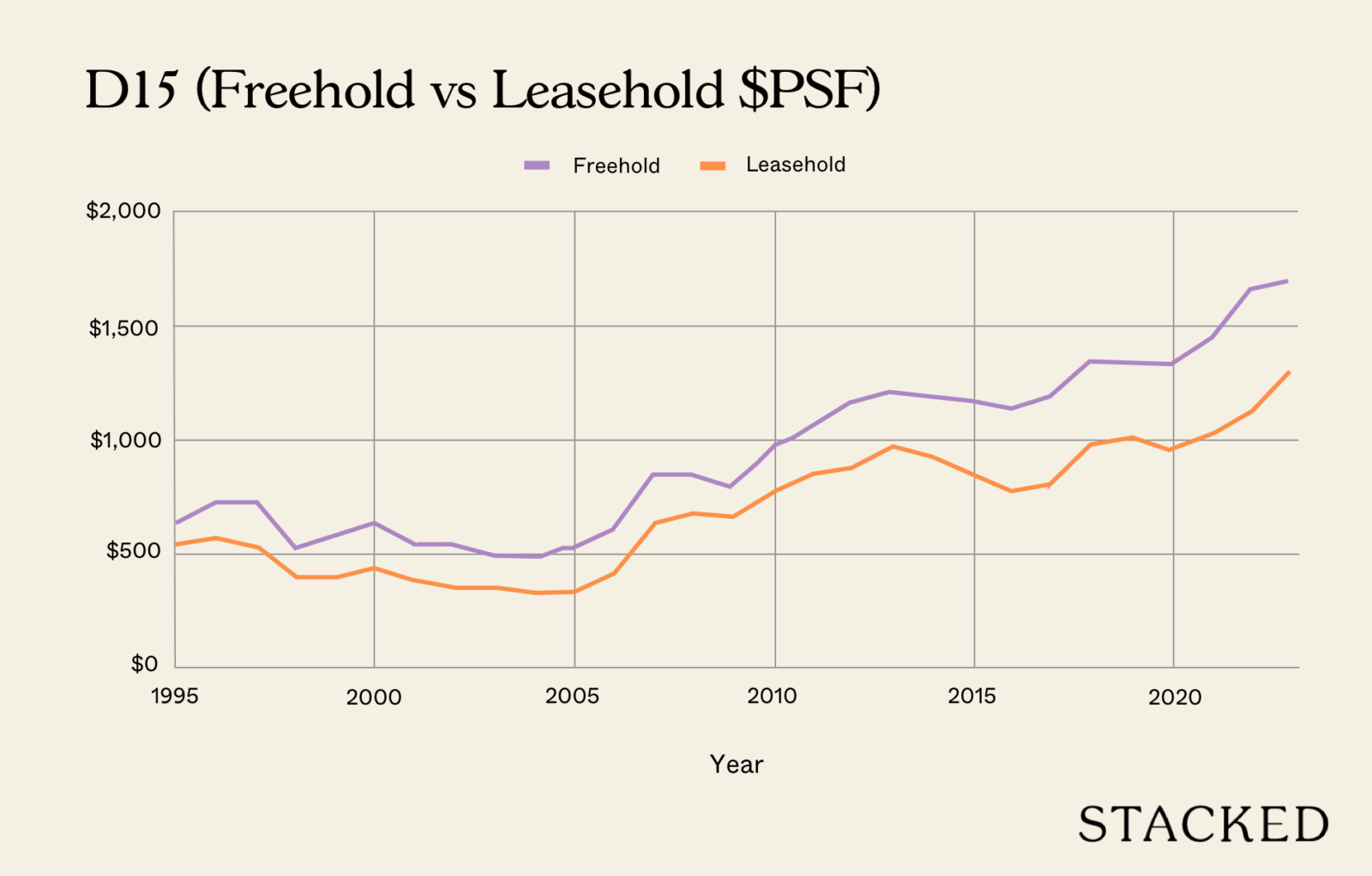

We can also go by district, in particular District 15 which has lots of older condos and more transactions:

Again, it's hard to draw a clear conclusion. The movement is sideways, compared to the much more obvious patterns in the landed segment.

However, when it comes to condos, it's difficult to predict if freehold units will mean better gains; especially when you factor in costs like freehold premium (they generally start off being around 20 per cent pricier than leasehold counterparts.)

Leasehold developments that are old may also sustain its high pricing if the market perceives it to have strong en bloc potential, so sellers aren't willing to let go of it at a lower price.

There's also an intangible factor at work: landed homes are niche, high-end properties. They're often bought by people who want a true family estate, and who may have no need to sell the property for gains.

There's a further status effect, in that foreigners can't buy landed property unless they get permission. That permission typically involves multi-million dollar contributions to the economy; so while the wealthy can brag of a leasehold Sentosa Cove bungalow, the wealthiest among them can brag about owning a freehold bungalow on the mainland.

ALSO READ: Tiong Bahru pre-war flat listed at $2m, lease left with just 43 years

This article was first published in Stackedhomes.