Old resale HDB flat vs new BTO: What's the difference?

Having stayed in an (old) resale flat for almost my entire life, I have grown accustomed to having sufficient space in my home.

However, as I’m at the stage where getting my own place is becoming a distinct possibility, I was reminded repeatedly that 'for my generation', space is not to be taken for granted (by my own family, no less).

This sparked some interest for me to delve deeper into seeing how HDB units have evolved since the olden days, especially after studying the phenomenon of shrinking void decks some time back.

If you read that piece, I’m sure you can tell by now my fascination with how spaces in Singapore have evolved over the last few years.

Whether it is for the best is still entirely up in the air, but what’s for certain is that things are not going to revert back.

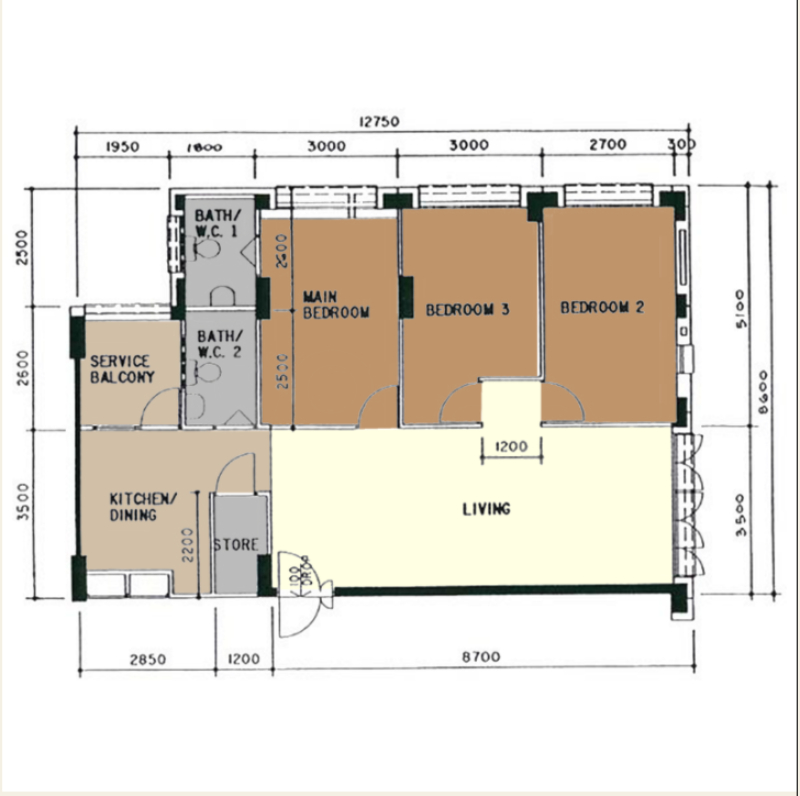

So to do this, I will be looking at two 4-room HDB units built some (approximately) 30 years apart, to identify some specific ways in which our flats have changed and the possible reasons behind these changes.

Let me introduce to you the two 4-bedroom HDB units up for inspection.

I’ll be honest, there wasn’t any real basis into why these two were chosen. Unless you count living a stone’s throw away as one!

For some context, 56 Cassia Crescent was completed in 1996 – making it 24 years old as at time of writing.

88A Dakota is a much newer project of course, where it is estimated to be completed in 2025, a part of Dakota One (a new BTO project).

Prior to looking at these floor plans, I was always skeptical about how much things could actually evolve, especially since it’s the same unit type after all.

Not to be dramatic about it, but it really is substantially different.

As you might expect, size is an obvious change – the 56 Cassia Crescent unit is 100 sqm (1,076 sq ft) while the 88A Dakota Crescent unit is 93 sqm (1,001 sq ft) – the other changes are more reflective of how times have changed.

In the past, I would say that the units really do promote a sense of communal living. This is apparent from the floor plan, since all the bedrooms are directly adjacent to the living room.

At the same time, the spaces are also largely open and rectangular, which does mean that everyone would feel more connected (as strange as it sounds).

On the other hand, you can clearly see that the 88A Dakota Crescent unit is all about providing privacy for all members of the family.

This is reflected in the T-shape layout of the communal spaces (the living and dining room), as well as a common corridor that leads to the rest of the rooms.

Also because of the more irregular shapes of the spaces (and therefore additional walls), the typical new BTO unit would feel more constricted.

In fact, the need for privacy for the modern family is pervasive even on the outside, as new HDB flats are designed such that windows open to views instead of the common corridor.

As a little bit of trivia for you, the building code regulations stipulating that all units need to have a household shelter was only enacted in 1996.

So the new BTO unit therefore comes with an irremovable shelter, while the resale HDB unit only has a small store room. No prizes for guessing which I prefer!

Another surprising discovery for me was how the bedroom sizes were distributed.

In the BTO unit, the spaces display a strong sense of hierarchy as the master bedroom is a lot larger than the other two bedrooms. Which yes, is a totally normal scenario today.

On the contrary, what’s really interesting here is that the sizes of the bedrooms are largely the same in the resale HDB unit – if you were to disregard the en-suite bathroom in the master bedroom.

This lack of hierarchy here, and the allocation of more space to the other bedrooms, might be one of the reasons why resale HDB units tend to provide a higher level of comfort for all members of the household.

For the younger ones reading this – you’ll know which one to push for.

Now that I’ve covered the changes, here’s some reasons why things are as they are now.

While land constraints is not a foreign concept to Singaporeans, it definitely has a hand to play in the constant shrinking of HDB units.

Back in the 80s, a typical 4-bedder was around 105 sqm (1,130 sq ft). This number then decreased to 100 sqm (1,076 sq ft) in the 90s, then to 90 sqm (968 sq ft) in the 2000s.

Given that we are working with a largely fixed amount of land to begin with and an increasing demand for more public housing, it is only natural that newly built units would be smaller.

Towards the end of the 20th century, the Singaporean Government began to launch different initiatives targeted at helping women balance work and family.

These initiatives included “increased maternity leave entitlements”, prevention of dismissal “without sufficient cause” and greater access to “part-time or flexi-work arrangements”.

In all, this allowed women to actually work, which in turn facilitated the birth of more dual-income families.

As incomes of both genders have grown exponentially since the turn of the millennium, private housing such as condominiums became viable, affordable options too.

This increase in demand for private housing is of course picked up by developers who proceed to churn out more housing options, fuelling the fast depletion of land in Singapore.

As the supply of available land continues to decrease, the only way to continue supplying public housing is thus to build smaller homes, with the dimensions of each room meticulously calculated to a tee to provide just enough space for daily activities.

Apart from supply-related issues, people’s priorities and preferences have also greatly shifted since 30 years ago.

There is now a greater desire for privacy displayed by Singaporeans of all ages, especially since we are now living in a world that is highly scrutinised and interconnected.

This particular need for privacy has also translated to our homes, where people usually want some distance away from their own family members, so that they could either work or recharge without any distractions.

Just like you’ve seen in the 56 Cassia Crescent unit, I believe privacy is definitely compromised, especially since the living room is directly outside every room.

Even if you were to stay in your room with the door closed, sounds from the living or even from your room will definitely be apparent to other family members.

As such, newer units tend to be more segregated, just like the 88A Dakota Crescent unit. Here, private and public spaces within the home are clearly demarcated with little to no intersections.

For instance, instead of building the common washroom in the kitchen as seen in the resale HDB unit, the bathroom here is placed strategically near the two bedrooms.

With a layout like this, it is true that everyone would be afforded with greater privacy, as additional walls tend to block out direct views and sounds.

It is of no wonder then that newer BTO units are built in this fashion.

In the past, the primary concern for the Housing Development Board was largely centered on building homes to meet the rising demands of Singaporeans.

Although there were efforts made to strengthen community identity, such as adding “distinctive features and new building designs”, many of these refreshing innovations took place on a “town and precinct level”.

On a smaller scale where we look at the units, the outlook is still more fixated on producing quantity, rather than quality. Thus, when you look at the resale HDB unit at 56 Cassia Crescent, the types of spaces provided only cater to tangible needs.

However, looking at the BTO unit at 88A Dakota Crescent, the design intentions appear to go beyond day-to-day needs, and this quality is translated in the presence of the household shelter.

Instead of just providing a storage space, the shelter is a precautionary feature that could protect the entire family should the unimaginable happen.

In addition to planning for disasters, more thought seems to be put into the arrangement of spaces. Specifically, the newer units are definitely designed with the modern family in mind.

Looking at the placement of the common bathroom in the BTO unit once again, it is clear that this location is more user-friendly for any family than if the washroom is situated in the kitchen.

It is adjustments like this that reveal how user interaction has definitely been taken into account over the years.

I guess for some people it’s like being caught between a rock and a hard place.

Privacy? Or openness and more space?

Personally, I do like the older layouts more. So if I really want to have a home that is more open, it is likely that I’ll have to look at older units, and perhaps do major renovations (which could in turn affect the resale prospect of my BTO unit in the future).

That said, I can’t help but wonder what would family life be like in the future, if BTO units tend to promote more introverted, private lifestyles.

Do I want that? Would you want that?

This article was first published in Stackedhomes.