Should Singapore adopt the Danish mortgage model?

With increasing mortgage interest rates, many Singapore homeowners locked with unfavourable interest rates or refinancing this year may be in for a rough ride.

Furthermore, they do not have many options - it's either bite the bullet and pay the higher mortgages or refinance at a potentially unfavourable rate with a bank. Some may opt to sell their property at a loss as they're unable to meet interest payments or higher maintenance fees.

In 2008, when the Global Financial Crisis hit, and the American and European mortgage-backed securities markets were on the brink of collapse, one property market survived relatively unscathed - the multi-billion-Euro housing loan refinancing market in Denmark.

While yes, there were some Danish banks that collapsed, they did not impact the local housing market as severely as other countries.

In fact, the Danish mortgage system coped extremely well - no mortgage banks (known as "special mortgage institutions") collapsed, there were no government bailouts, and the Danish government did not need to step in to guarantee the issuance of mortgage bonds.

Wait… mortgage bonds? How are they linked to housing loans?

A bond is a fixed-income, interest-yielding financial instrument that acts as a loan to institutions and governments so that they can utilise the liquidity to finance projects and operations.

The bondholder, or investor, earns coupon payment interest, throughout the tenure of the bond. In Singapore, you'd be familiar with bonds like the Singapore Government Securities (SGS) bond and the Singapore Savings Bonds.

Anyway, upon bond maturity - ie. tenures typically last for five years or as long as 30 years - the borrower (the institution or government in this case) will return the face value amount to the bondholder (which could be investors like you, me or fund managers).

Similarly, a mortgage bond, or mortgage-backed security (MBS), is a loan backed by a housing-related asset (like mortgages).

For most bond issuers, including the ones selling MBS in Singapore, these assets are usually a basket of different collaterals, hence the term "covered bonds". There are many such MBS for sale here, from Exchange Traded Funds, Real Estate Investment Trusts (Reits) to Depository Receipts.

However, the MBS we know of in Singapore, is different from the mortgage bonds sold by specialised mortgage banks in Denmark. Why? They're tied to the home loan applicant directly.

1. In Singapore, the banks bear the risk whenever you secure a loan for your house. You service the home loan by repaying your mortgage monthly with interest. If you default on the loan, the bank has the right to seize the property from you, because the loan amount is derived largely from the bank's customer deposits.

2. In Denmark, when you want to get a home loan, you approach a "specialised lender" or "special mortgage institution". These institutions are not permitted to take deposits (ie. they're not like traditional banks), but are established to exclusively sell bonds secured against property assets, like houses, offices, commercial buildings and so on.

3. These lenders will then match-make you (the borrower) with specific mortgage bond buyers. The borrower can fund 80 per cent of their home purchase through these bonds (with fixed or adjustable interest rates) and make up the remaining 20 per cent through savings or bank loans.

4. This "pass-through" system minimises the mortgage banks' exposure by transferring the interest rate volatility and risks to both borrowers and bondholders.

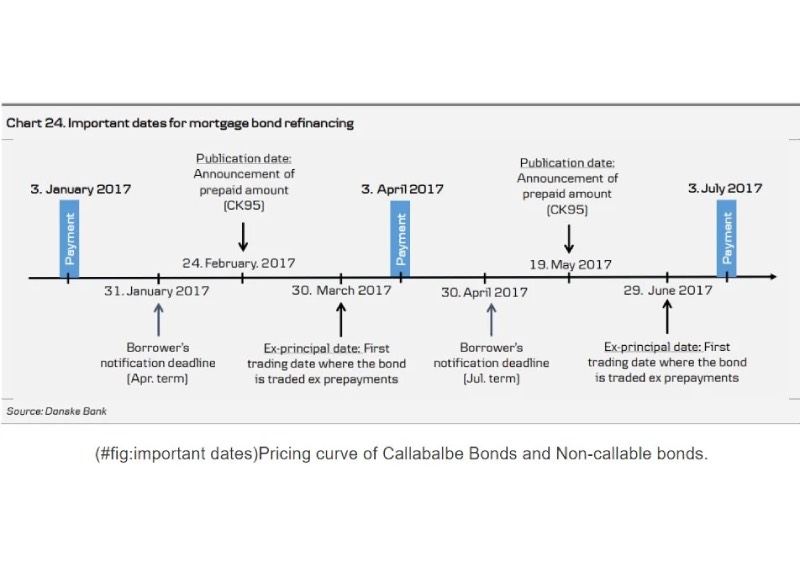

5. Depending on the terms, the borrower makes quarterly repayments with interest for the duration of the bond while the bondholder receives coupon interest payments until maturity. However, the borrower is permitted to make early prepayment without penalties.

If a borrower defaults on his loan, the mortgage bank may put the property up for a forced sale (the process takes six months). However, the beauty of the bond market is that the borrower has options when it comes to reducing his or her liability.

By linking bonds and borrowers, an active secondary market is formed. Because the borrowed amount mirrors the bond, homeowners can monitor bond prices and time when they would like to refinance their loans (the bond market decides the interest).

In 2019 and during Covid, the demand for these bonds was so great, that short-term interest rates fell below zero (yep, negative interest rate). Including taxes and fees, a borrower would pay significantly less in interest payments over time.

Also, 30-year fixed interest rates fell to as low as 0.5 per cent. This galvanised many borrowers to buy up long-term bonds. They can also repurchase their own loans at market price, which further adds liquidity to the bond market.

So if a Danish homeowner secured a $500,000 30-year fixed rate mortgage at three per cent interest, he has to pay $2,108 per month for 30 years to repay the loan. But if interest rates rise to six per cent, the mortgage bank should be willing to let him buy his mortgage for $358k - because that's what the market is willing to pay on the securitised mortgage.

In 2022, as US and other central banks increased interest rates, savvy borrowers were able to refinance their loans with these lower fixed-rate bonds at below issuance price to cut their debt. This also benefits the bondholder as lower debt means lower credit risk.

Borrowers can also refinance at par with the same mortgage institution even if their home equity has declined because of a fall in home prices. As long as they do not extend the term of the loan or increase the principal amount, a property appraisal is not needed.

Lastly, homeowners can transfer his or her mortgage to a buyer as part of a property sale, which is useful in a high-interest-rate environment. They can now offset their next home purchase due to a higher capital gain. This incentivises buying and selling, rather than locking-in homeowners as they wait for interest rates to improve.

This right to early repayment of their loans through a bond market is unique to Denmark.

Today, the Danish mortgage-backed bond market is worth roughly 450 billion euros. It was reportedly 123.6 per cent of Denmark's GDP in 2021.

Interestingly, Bloomberg reports that in 2022, foreigners owned almost a quarter of these Danish "mortgage bonds". This is because these "covered bonds" are deemed extra-safe due to a balanced principle of shared risk between lender and borrower.

Despite differences in landmass, Singapore and Denmark share almost equal population sizes - 5.454 million vs 5.857 million.

Denmark's currency, the krone, is pegged to the Euro at a rate of 7.45 to one.

Lauded as an exemplary mortgage model that has stood the test of time and crisis, many countries, including the Netherlands and USA, have written theses and analyses on whether this model, or parts of it, can be introduced in their own housing economies.

According to these analyses, the model has stricter requirements:

Truth be told, most of these measures are not unfamiliar to Singapore's property environment.

The upside is that there is a long-term retention of funds invested in the housing market and circulating through the economy (we are constantly looking to attract foreign investors into our country, right?).

Notably, these funds didn't come through banks, but through bondholders, who are attracted by the extra-safe investment opportunity these mortgage-backed securities offer.

As we've seen with the Danish market, many of these bondholders include foreign investors.

With such a model, borrowers have more options when it comes to making early repayment or when interest rates fluctuate in or against their favour. They do not need to wait three to four years on the tenure to plan their refinancing options.

In summary, the Danish mortgage model reflects a possible alternative. But introducing it into an existing housing mortgage model is not easy. It requires policy-making, political will and definitely a common-interest goal among all affected parties.

The question probably is whether such a model works for a society like ours.

What's clear is that this "balance principle" spreads risk across different parties. To any homeowner or investor, that's a win-win in their books.